Puberty Menorraghia: Causes and Management

M3 India Newsdesk Aug 06, 2024

Excessive menstrual bleeding during puberty, known as puberty menorrhagia, occurs in the few years following a girl’s first period(menarche). This article discusses the causes, diagnosis and management of puberty menorrhagia.

Menarche

Menarche, the onset of the first menstrual period, is a pivotal moment in adolescence. It marks the beginning of reproductive maturity and is a major developmental milestone during puberty.

Although the exact triggers of puberty and menarche are not fully understood, they are influenced by genetics, nutrition, body weight, and the development of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis. This axis can take up to two years to fully mature. During this period, it is normal for adolescents to experience menstrual irregularities. [1]

Puberty menorrhagia

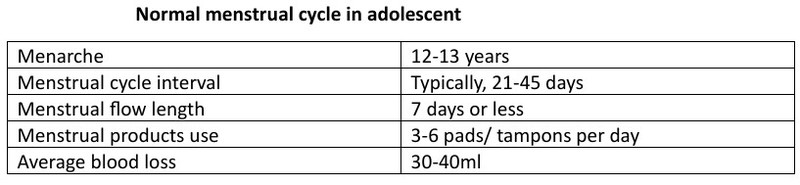

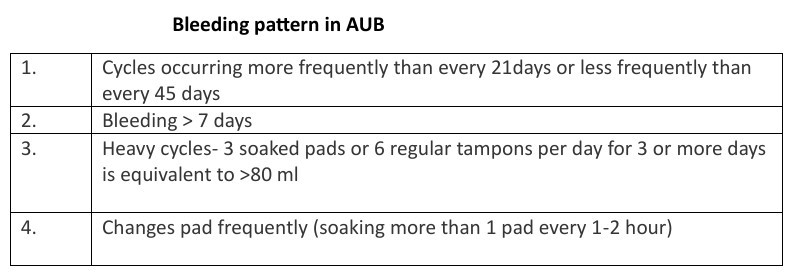

Puberty menorrhagia involves abnormal uterine bleeding in terms of duration, volume, frequency, or regularity. It is a prevalent issue among hospitalised adolescents, constituting around half of the gynaecological concerns in this age group. Monitoring the menstrual cycle should be considered an important aspect of routine paediatric visits for adolescents.

PALM-COEIN classification

Heavy menstrual bleeding is the most common way abnormal uterine bleeding shows up in medical practice. FIGO defines the aetiology of AUB using PALM-COEIN classification. PALM refers to structural pathologies like Polyp, Adenomyosis, Leiomyomas and Malignancy or atypical endometrial hyperplasia and COEIN encompasses non-structural pathologies like Coagulopathies, Ovulatory disorders, Primary Endometrial disorders, Iatrogenic and Not otherwise classified. Interestingly, in young girls, the structural causes (PALM) are rarely the reason behind abnormal uterine bleeding. [2]

Causes

- There are two most common causes of abnormal uterine bleeding in adolescents, first is anovulatory cycles (95%) due to immature hypothalamus.

- In the first three years after starting mensuration, about half of the menstrual cycle is anovulatory. However, by the fifth year post-menarche 75% of the cycles become ovulatory. This early anovulation is attributed to a lack of progesterone secretion from the ovarian follicles and excessive estrogen (E2) production. [3]

- The second most common cause of AUB is reported to be coagulopathies (5-28%) in which Von Willebrand disease (5-48%) is the most common.

- In declining order, additional causes of coagulopathy include platelet dysfunction (2-44%), thrombocytopenia (13-20%), coagulation factor deficiencies (8-9%), followed by smaller incidences of leukaemia, hypersplenism, and hereditary bleeding disorders. [3]

- To investigate heavy menstrual bleeding, it is crucial to rule out endometrial causes when menstrual cycles are regular and predictable (AUB-E).

- Pharmacological treatments affecting the endometrium, such as gonadal steroids and OCPS may lead to bleeding episodes (AUB-I). Uncommon abnormalities like arteriovenous malformations fall into the “not otherwise classified” category for abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB-N). [2]

Diagnosis

- Detailed menstrual history is the keystone.

- Clinical examination, appropriate lab investigations and imaging procedures are important for the evaluation of AUB.

- A pelvic examination cannot be performed on sexually inactive girls.

- Pregnancy must be ruled out, and assessment for anaemia and bleeding disorder should be conducted.

- Endocrine disorders also need to be excluded.

- Screening for sexually transmitted infections is essential in sexually active girls.

- An ultrasound should be performed to measure endometrial thickness to help diagnose or exclude PCOS.

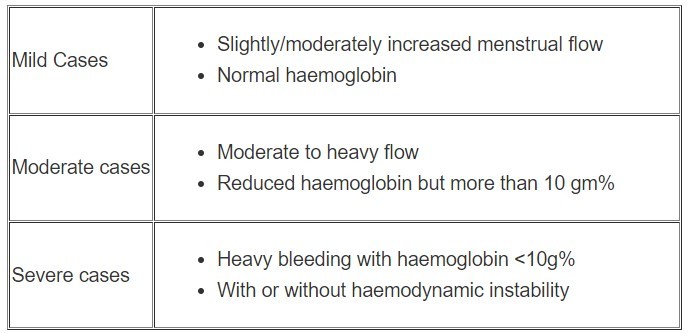

- The primary focus of treatment revolves around ensuring stable blood circulation, correcting anaemia, and maintaining regular menstrual cycles.

Management

Mild cases typically require reassurance, an explanation of the underlying cause, iron supplements, keeping a menstrual diary, using NSAIDs and tranexamic acid during periods, and periodic check-ups. In moderate cases, it's important to investigate other potential causes, start hormonal therapy, and provide iron supplements.

Severe and acute cases may necessitate hospitalisation if the patient is unstable or experiencing heavy bleeding. Initial measures to achieve haemostasis include non-hormonal treatments such as tranexamic acid, hormonal therapies, and, if necessary, blood transfusions. [4]

In managing acute cases in adolescents, initial treatment typically involves medical options, and procedural intervention is considered for those who do not respond to medical therapy.

Treatment choices depend on the cause of bleeding, the patient's clinical stability, and any underlying medical conditions. Hospital admission is necessary for haemodynamically unstable or actively bleeding patients. Management includes fluid resuscitation using crystalloid solutions, hormonal therapy, and blood transfusions as needed.

By the time girls experience their first menstrual period (menarche), they have typically completed 95% of their growth. Therefore, worries about using estrogen and its potential to prematurely close the growth plates should not deter the use of hormonal therapies for treating heavy menstrual bleeding.

Treatment

- Treatment options for heavy menstrual bleeding with hormonal therapy include intravenous conjugated estrogen administered every 4-6 hours, or monophasic combined oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) containing 30-50 mcg of ethinyl estradiol, taken every 6-8 hours until bleeding ceases.

- After the bleeding stops, typically within 24-48 hours, a tapering regimen of combined OCPs can be initiated.

- Alternatively, progesterone-only therapy is another option, with medroxyprogesterone acetate given at 10-20 mg every 6-12 hours, or norethisterone acetate at 5-10 mg every 6 hours. Additionally, a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (LNG-IUD) can be considered for sexually active adolescents. [5]

- In cases where hormonal therapies are not suitable or ineffective, non-hormonal treatments like antifibrinolytic agents such as tranexamic acid or aminocaproic acid can be administered orally or intravenously.

- Blood transfusion is reserved for patients who are haemodynamically unstable.

- For individuals with bleeding disorders, consultation with a haematologist is recommended.

- When medical treatments fail to control heavy bleeding and the patient remains unstable with significant bleeding, doctors may consider procedural interventions.

- Options include placing an intrauterine balloon for 12-24 hours or performing uterine evacuation to avoid more invasive procedures.

- In severe and life-threatening situations, procedures like endometrial ablation, uterine artery embolisation, or hysterectomy may be necessary, although these interventions can potentially lead to infertility. [6]

Conclusion

- In conclusion, puberty menorrhagia, characterised by excessive menstrual bleeding shortly after menarche, represents a significant health concern during adolescence. While often attributed to anovulatory cycles and coagulopathies, its management requires a comprehensive approach tailored to each patient's clinical presentation and underlying causes.

- Treatment focuses on stabilising haemodynamics, correcting anaemia, and restoring regular menstrual cycles through hormonal and non-hormonal therapies. Procedural interventions like endometrial ablation or hysterectomy are reserved for severe cases where other treatments have failed or when life-threatening bleeding occurs, albeit with potential implications for fertility.

- As clinicians navigate the complexities of treating puberty menorrhagia, ongoing education and supportive care for adolescents and their families remain crucial in promoting health and well-being during this critical developmental stage.

Disclaimer- The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of M3 India.

About the author of this article: Dr Nikita is an Assistant Professor in the OBGY department at SMMCHRI in Chennai.

-

Exclusive Write-ups & Webinars by KOLs

-

Daily Quiz by specialty

-

Paid Market Research Surveys

-

Case discussions, News & Journals' summaries