Management of Acute Sore Throat: Expert Consensus Recommendations

M3 India Newsdesk Apr 26, 2023

Most often in primary health care, an acute sore throat is a common cause for visits to a health care practitioner. Experts from several nations representing various traditions have recently produced a consensus that has provided recommendations.

Key takeaways

- The current standard of care includes triaging patients with acute sore throats. This study's primary addition to the literature is a clarification of the sort of triage that is necessary and a detailed explanation of how it should be carried out in order to safely decrease the prescription of antibiotics and to focus on the few individuals who could benefit from antibiotic therapy.

- In an environment with a low risk for rheumatic fever, patients with an acute sore throat that seems to be simple and low clinical scoring (Centor score 0-2 or FeverPAIN 0-2) do not need testing for the presence of GAS or an antibiotic prescription.

- Patients with an acute sore throat that seems to be uncomplicated and a higher clinical score may either be tested and treated if the results are positive or they can utilise an approach of waiting and watching.

Antibiotics are overprescribed to individuals with an acute sore throats for a variety of reasons, including patient demand and concern about consequences.

In high-income nations, all sore throat treatment recommendations urge caution while using antibiotics. Furthermore, group A beta-haemolytic Streptococcus (GAS) is the focus of almost all recommendations. The recommendations of guidelines on the therapy of individuals with an acute sore throat, however, vary greatly in a number of areas.

Point-of-care testing (POCT) guidelines for detecting the presence of GAS are one important difference. Contradictory recommendations based on the same body of information are illogical, may confuse patients, and result in unnecessary therapeutic care variance.

The cause of acute sore throat

Acute sore throat patients often have different viruses present in 30% of cases, GAS in 7–30%, and no apparent culprit in 30% of cases. Recent research has shown that individuals with sore throats in teenagers and young adults usually have bacteria like Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis, Fusobacterium necrophorum, and other microorganisms.

Almost no healthy individuals have GAS. Consequently, it is more likely to be the aetiologic agent than a commensal when identified in an adult with a sore throat. Children are significantly more likely than adults to have commensal GAS.

Post-sore throat complications and consequences

Without antibiotic therapy, about four out of five people recover from a sore throat within a week. Sore throats are often self-limiting illnesses.

Suppurative side effects from a sore throat may infrequently include peritonsillar abscess (quinsy), otitis media, sinusitis, and sepsis. Additionally, skin infections may happen, usually in low-income environments. In adolescents and young adults with quinsy, suppurative consequences are predominantly associated with GAS but also with F. necrophorum. The Lemierre Syndrome, which is characterised by internal jugular suppurative thrombophlebitis and metastatic emboli most often to the lung, is the most dangerous yet infrequent complication linked with F. necrophorum.

Rheumatic fever and glomerulonephritis are non-suppurative consequences, mainly associated with GAS. A feared consequence that often results in mortality, mainly in children and young people in low-income countries, is rheumatic fever and consequent rheumatic heart disease.

In environments where rheumatic fever risk is high, antibiotic therapy of individuals with a sore throat lowers the incidence of future rheumatic fever.

Antibiotic therapy

Targeting antibiotics to patients where the benefits exceed the risks is crucial due to the many possible negative effects of antibiotics and worries about the rise in antibiotic resistance.

The majority of empirical research demonstrates that adult patients with GAS respond to antibiotics more often than adults who do not. Children with GAS who get antibiotic therapy seem to have fewer recurrences. For lowering acute symptoms in kids with GAS, there is conflicting data.

In conclusion, adult patients with GAS are found to have the greatest evidence for the impact of antibiotics on symptoms in individuals with acute sore throats. In children with GAS and in adults with S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis, the evidence is weaker. Antibiotics do not seem to have any impact on the duration or severity of acute symptoms in either adolescents or young adults who are carrying S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis or youngsters who are carrying F. necrophorum.

According to the available research, people who have GAS detected in throat swabs should typically get antibiotic therapy when judged required. It may be pertinent to discuss S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis and F. necrophorum for certain individuals with possibly detrimental acute sore throats.

Finding GAS-positive patients

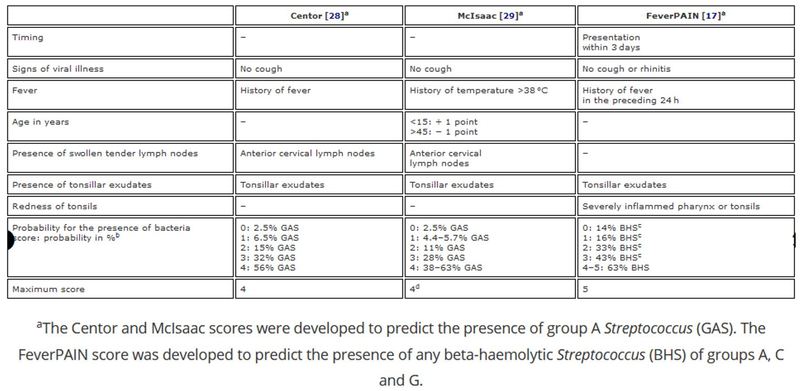

To determine whether patients have a high, moderate, or low likelihood of harboring GAS, several scoring systems, including the Centor scores, the FeverPAIN scores, and the McIsaac scores, were devised. When algorithms are utilised as stand-alone techniques, their capacity to distinguish between patients who have or do not have GAS may not be at its best.

Potentially harmful bacteria, including GAS, may be found using throat swabs. Swab samples submitted to a lab for examination, however, are hampered by the protracted wait for the results. Modern, high-quality POCTs may provide results in a matter of minutes and offer sensitivity and specificity that rival traditional culture.

The use of POCT to identify GAS has been the subject of many myths and misunderstandings in the past. The main justification for utilising a POCT is to prevent improper antibiotic prescription in individuals with an acute sore throat that seems to be simple. Due to the increased percentage of GAS carriers in children compared to adults, identifying GAS is a secondary purpose of POCT that may be useful in adults but may perform less well in children.

Prioritisation of patients with acute sore throats

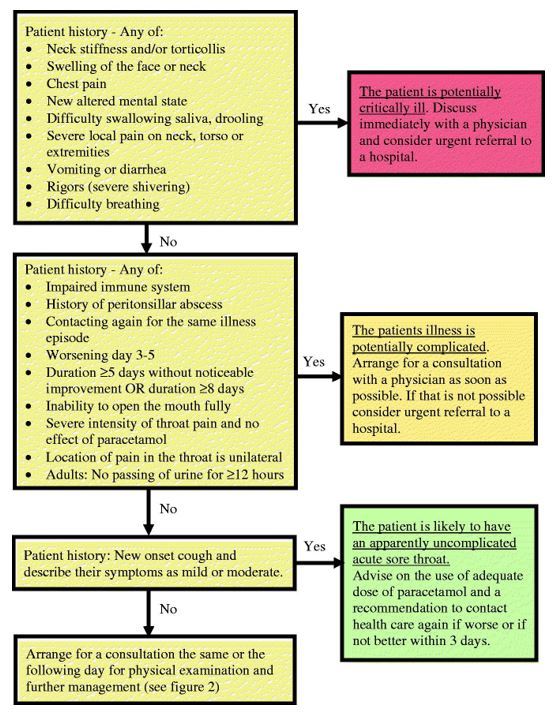

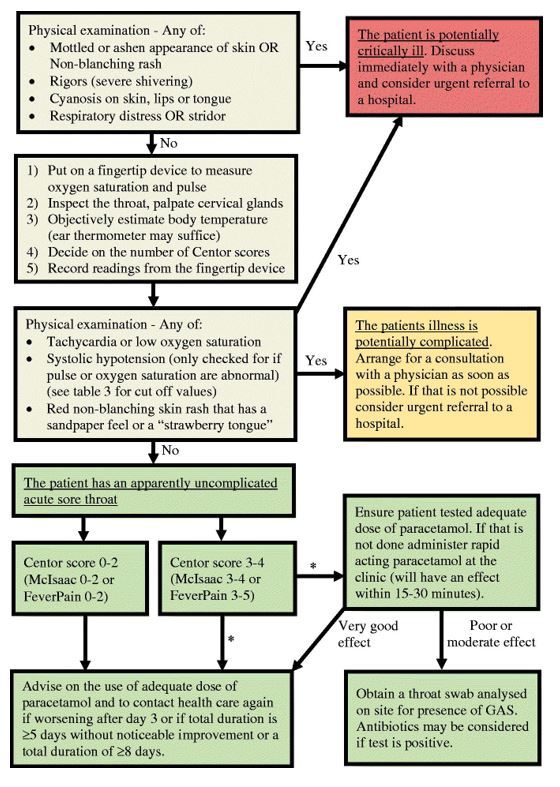

In many clinics nowadays, triaging patients who arrive with an acute sore throat is a regular procedure. Triage plans may have a variety of contents, but the most have a strong emphasis on detecting patients who are more likely to be carrying GAS. Although recommendations advise against it, the incidence of antibiotic prescriptions is still high, and this calls for a clarification of proper triage. A novel triage system, including adequate safety netting, is presented in a consensus paper that was published recently and may help to lower the excessive levels of antibiotic prescription currently in place.

According to the paper, a key factor in the overprescription of antibiotics is the inability to accurately discern between individuals with an acute sore throat that seems to be straightforward and those who may have complications.

Due to this, experts suggest a new triage system for patients with acute sore throats in order to identify those who are initially at risk for suppurative complications or sepsis as well as those who are subsequently at risk for sequelae such as rheumatic heart disease. Depending on their risk for acute suppurative consequences as well as their subsequent risk for rheumatic fever, this evaluation results in a distinct therapy.

Too many patients will likely be treated as if they are potentially complicated if it is not possible to distinguish between patients with seemingly straightforward acute sore throats and those who may be complicated, which will lead to the inappropriate prescription of antibiotics.

A key takeaway from the above figures is that individuals with an acute sore throat that seems to be uncomplicated and a low clinical score shouldn't undergo testing or be given antibiotics. If a POCT is positive, those with a higher clinical score may either be tested and treated, or a wait-and-see approach can be utilised.

Regardless of whether patients initially diagnosed with an acute, uncomplicated sore throat are given antibiotics, they should always be told to call their doctor if their symptoms worsen on day 3 after the onset of their illness, do not noticeably improve after five days, or last for a total of fewer than eight days. If they relapse with illness, they should be diagnosed with a possibly complicated acute sore throat.

Possibly problematic acute sore throat

- In order to determine if there are any possible problems or diagnoses needing special treatment, patients with potentially problematic acute sore throats need to be evaluated.

- Some signs point to the potential for suppurative consequences, which might indicate a complicated acute sore throat.

- Worsening symptoms after 3 days (including after antibiotics), being unable to completely open the mouth, unilateral neck oedema, rigours (shaking chills with a high likelihood of bacteraemia), and dyspnea are all warning indications.

- Particularly in teens and young adults, patients with these symptoms need thorough examination, often with imaging, and it may be pertinent to screen for the presence of S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis or F. necrophorum.

- Peritonsillar abscess is the most frequent significant suppurative consequence.

- Most typically, it affects teenagers and young adults (15 to 30 years old). In very few instances with fast deterioration, it is important to keep the very uncommon Lemierre Syndrome in mind.

Some people have sore throats and tiredness symptoms for a longer period of time. One should take viral illnesses like infectious mononucleosis and, in rare instances, acute HIV into consideration in these individuals with potentially complex acute sore throats. Recently, the monkeypox virus has drawn attention because its symptoms might resemble those of a severe sore throat.

Treatment of individuals with moderate or increased risk of rheumatic fever

Patients first need the same triage as was previously stated. To lower the risk of acute suppurative complications and sepsis, patients who are potentially critically unwell or who have potentially complex acute sore throats need to have the appropriate diagnosis and therapy, as mentioned above. The possibility of developing rheumatic fever, later on, must also be taken into account.

Patients with an acute sore throat that seems to be simple but who have a moderate to high risk of developing rheumatic fever need to be managed in a way that minimises that risk. Even in environments where there is a known moderate or high risk for rheumatic fever, clinical judgment alone without the use of POCT to identify GAS is likely to leave a significant number of patients suffering from GAS without antibiotics.

Therefore, regardless of the clinical GAS score, if POCT is available, experts advise testing all patients deemed to be at moderate or high risk for rheumatic fever and prescribing antibiotics to all patients harbouring GAS. In situations when there is a high risk of rheumatic fever, it is advised that all patients with acute sore throats take antibiotics if POCT is not available. Antibiotics should be provided to patients with a clinical score suggesting the likelihood of the presence of GAS, such as Centor scores 2-4 or FeverPAIN scores 2-5, in settings with moderate risk where POCTs are not available.

Disclaimer- The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of M3 India.

About the author of this article: Dr Monish Raut is a practising super specialist from New Delhi.

-

Exclusive Write-ups & Webinars by KOLs

-

Daily Quiz by specialty

-

Paid Market Research Surveys

-

Case discussions, News & Journals' summaries