Intermittent Fasting: Clinical Evidences Part 2

M3 India Newsdesk May 30, 2024

This article examines the physiological benefits of intermittent fasting (IF). It highlights how IF may offer a sustainable long-term approach to health improvements while also discussing potential side effects and the importance of tailored dietary and exercise plans.

In the previous part of this article, we got to discuss in brief, the basic concept and types of intermittent fasting (IF), its difference from caloric restriction (CR) and the physiological changes that drive the potential benefits of IF.

In this concluding part of the article, we will venture into understanding the effects on the hormonal systems of the body, various disease processes and the current evidence.

We would also try to shed some light on how diet protocols fail in the long term and IF might be a potential longer-term approach to similar health goals as diet/CR and more.

IF and weight loss, obesity, prediabetes, diabetes and metabolic syndrome

The primary reason to adopt CR or IF was their beneficial effect on weight. A high carb (especially refined or simple carbs) load in food causes a spike in postprandial glucose levels. About 80% of the presented load is taken care of by the muscles, brain and other tissues postprandially and about 20% is processed by the liver.

- The excess amount is processed to adipose tissues as stored fat. To manage the high loads of glucose, the insulin levels rise, however, if the presented glucose load remains high, after a certain point the liver fails to manage the load which in turn leads to the development of steatohepatitis (fatty liver) and subsequently insulin resistance (leading to poorer glucose uptake in insulin-dependant tissues). On the other hand, fructose must be fully processed by the liver alone.

- The commonest sources of fructose in our diet are the table sugar (sucrose) that we consume (chemically one part and one part fructose) and fructose-rich corn syrup, a very cheap component in processed foods. Fruits that we usually consume provide only about 15-20 g of the daily fructose load (which now has gone substantially to the tune of more than 40-50g per day, particularly in Western countries; ours not being far behind).

- It is also now proven that glucose is as good as cocaine in giving us the dopamine kick, and development of tolerance and as bad (probably worse) as cocaine in causing withdrawal [11]. Hence our craving for sugar keeps bringing us back to sugary/sweet/high glycemic index foods.

- Hence the vicious cycle of glucose and fructose-rich food, hyperinsulinemia, steatohepatitis and an overloaded liver gives rise to insulin resistance, and the results thereafter need no elaboration.

- When “dieting” in the form of CR is done, our brain (which doesn’t understand the difference between voluntary reduction in food intake and a famine) drives our body into conservation mode leading to reduced basal metabolism (feeling tired, cold or sometimes having lower heart rate than usual) and dials up the ghrelin levels.

- This leads to feeling hungry all the time and we tend to steer away from the designated path in the long term and go back to consuming more calories and gaining back weight. This is the “yo-yo” effect of dieting.

- IF on the other hand, reduces the caloric intake by increasing the time interval between meals. The body, however, learns to turn the “metabolic switch” on and switch to alternate modes of energy (ketones) by then and hence the metabolism doesn’t slow down.

- During this period, the glucose (and fructose) load to the body reduces and the insulin levels fall, leading to lesser resistance and reduction in visceral adiposity. Not only this, leptin (satiety stimulant), Adiponectin (improves insulin sensitivity) and Vaspin (visceral adipose tissue-derived serine protease inhibitor which attracts attention as an insulin-sensitising adipokine) levels increase in subjects on IF improving insulin sensitivity and steatohepatitis[5,12].

These mechanisms have beneficial effects on weight, waist circumference (WC), glycemic variability, and A1c among other benefits which we will discuss shortly.

IF and cardiometabolic health

Insulin resistance is a pro-inflammatory state associated with raised C-reactive protein, decreased adiponectin, lower low-density lipoprotein (LDL) particle size, etc that ultimately contribute to or are associated with the development of atherosclerosis and coronary artery disease [5,13].

Insulin is also associated with atherogenic dyslipidemia and increases the risk of fluid retention and congestive heart failure [5,14]. Therefore, it would be expected that cutting insulin levels with intermittent fasting will lower serious adverse cardiovascular events.

- IF and lipids

It has been demonstrated that nuclear expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α (PPAR-α) and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator 1 α in the liver increases fatty acid oxidation and Apo A production while decreasing ApoB synthesis.

Also, there is higher fatty acid oxidation lower hepatic triglycerides and very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) production. Altogether, these physiologic changes may help reduce serum levels of VLDL, LDL-C, and small dense LDL-C (sdLDL) [5,15].

- IF and hypertension (HTN)

Reduction in blood pressure in the setting of IF may be associated with the activation of the parasympathetic system, due to higher activity of the cholinergic neurons of the brainstem [16].

While brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is primarily produced in response to glutamatergic receptor activation, studies show that IF is a key environmental stimulus [17].

- IF and inflammation

Adiponectin levels fall in multiple pathologies, including atherosclerosis, insulin resistance, T2DM, and coronary disease. With IF, there is an increase in adiponectin secretion [16]. Adiponectin has anti-atherosclerotic and anti-inflammatory effects via inhibition of monocyte adhesion to endothelial cells.

It also inhibits the release of vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1), endothelial-leukocyte adhesion molecule 1 (ELAM-1), and intracellular adhesive molecule 1 (ICAM-1) on vascular endothelial cells, with an overall result of reducing local and systemic inflammation [16].

IF and cognition, neurodegenerative diseases and longevity

- Ezzati et al. [18] summarised evidence on associations between obesity and the risk of cognitive decline, including Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia.

- IF can improve cognitive function through various mechanisms, including regulation of the circadian rhythm and increasing autophagy, leading to decreased neuroinflammation, decreased oxidative stress, and increased insulin sensitivity [19].

- Switching the metabolic switch on (lipid synthesis and storage to the mobilisation of fat through fatty acid oxidation and fatty acid-derived ketones) and weight loss can independently improve cerebrovascular function and cognitive function [20].

- Mitochondrial dysfunction is associated with cognitive impairments in studies of ageing brain and neurodegenerative diseases, and it may act by enhancing mitochondrial biogenesis and by regulating mitochondrial dynamics [21]. Therefore, IF may be a strategy.

- To lengthen life and postpone neurodegenerative diseases by enhancing mitochondrial function.

The metabolic effects of IF are summarised below:

Reproduced from Mishra S, Persons PA, Lorenzo AM, Chaliki SS, Bersoux S. Time-Restricted Eating and Its Metabolic Benefits. J Clin Med. 2023 Nov 9;12(22):7007. doi: 10.3390/jcm12227007. PMID: 38002621; PMCID: PMC10672223

Reproduced from Mishra S, Persons PA, Lorenzo AM, Chaliki SS, Bersoux S. Time-Restricted Eating and Its Metabolic Benefits. J Clin Med. 2023 Nov 9;12(22):7007. doi: 10.3390/jcm12227007. PMID: 38002621; PMCID: PMC10672223

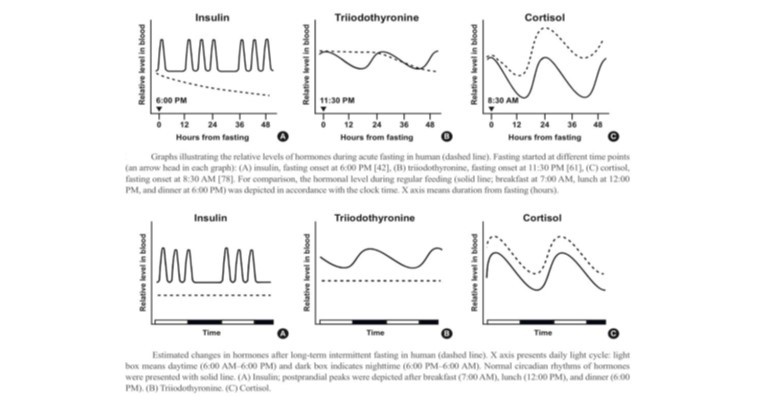

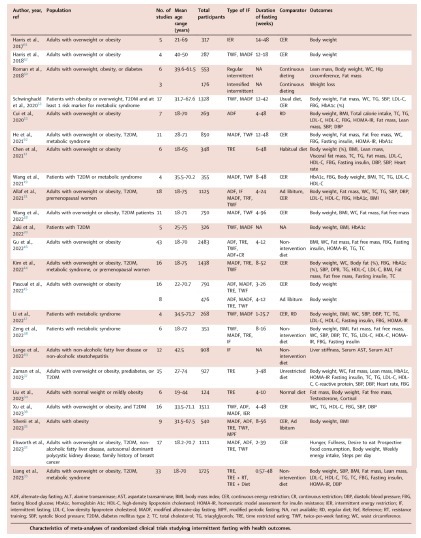

IF and its effect on circadian rhythms of hormones

Although robust data is lacking in this area, IF has been seen to affect the circadian rhythms of various hormones in the body (observed both in rat models and humans) The following figures summarise these effects.

Reproduced from Kim BH, Joo Y, Kim MS, Choe HK, Tong Q, Kwon O. Effects of Intermittent Fasting on the Circulating Levels and Circadian Rhythms of Hormones. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul). 2021 Aug;36(4):745-756. doi: 10.3803/EnM.2021.405. Epub 2021 Aug 27. PMID: 34474513; PMCID: PMC8419605

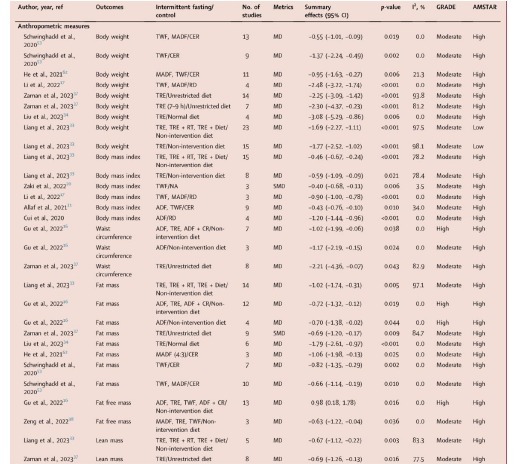

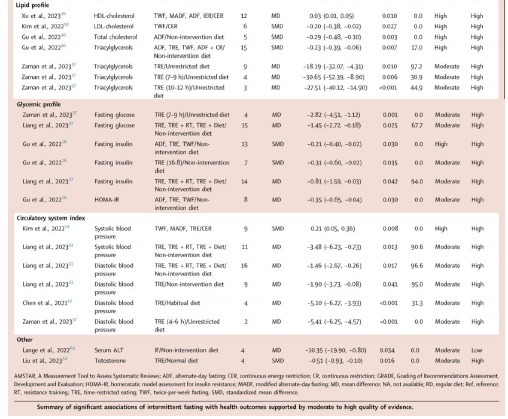

Most recent data on IF

The biggest limitation of most of the studies was a smaller sample size and lack of randomised control trials (RCT). In recent times, many RCTs, systematic reviews and meta-analyses have been published.

Most recently, in March 2024, Sun et al [3] published a very comprehensive umbrella review of a huge number (about 2234 studies, including many meta-analyses and systematic reviews) of studies relating to IF and its health benefits.

They conclude that IF could beneficially affect a range of health outcomes (decreased waist circumference (WC), fat mass, LDL-C, triglycerides (TG), total cholesterol (TC), fasting insulin, and systolic blood pressure (SBP); increased HDL-C and fat-free mass (FFM) for adults with overweight or obesity compared to CER or non-intervention diet.

Having discussed the benefits of IF, it's important to know what are the possible downsides (side effects):

- Since very few, long-term studies are available for IF, it is difficult to comment upon the long-term effects and problems associated with IF.

- However, as per current studies, one of the less frequent but documented side effects is hypoglycemia which can be mitigated by the correct choice of food during the eating periods. It is hence important to initiate individuals on IF regimens in a GRADED manner by slowly adjusting fasting intervals over a few weeks, especially in diabetics.

IF provides multiple benefits, but just maintaining a fasting period in between meals doesn’t ensure the potential benefits. It is equally important to consume the right type of food for it to be successful.

Also, “unrestricted” eating doesn’t translate to “unlimited” eating. The food must be a healthy mix of proteins, fats and carbs some advocate a higher proportion of proteins and fat than carbs, and within the calculated daily caloric need of the person.

A common query that comes while discussing IF is what can be consumed during the fasting periods. The consensus is that black coffee, black tea and water can be consumed during fast periods.

It is important to avoid refined and processed carbs, oils and fats during eating periods and in general for all individuals. Aerated beverages or beverages with artificial sweeteners should also be avoided.

Another query that arises is that of exercise during fasting. While it is a discussion on its own, in a nutshell, exercising in the fasting state could have more benefits than in the fed state. It adapts the body to be able to utilise fatty acids and triglycerides during the workouts (especially with moderate-intensity workouts).

Having said that, naïve individuals need to be carefully introduced to this process by first increasing the timing and then the intensity to avoid complications.

Also, it's important to know which group of individuals should avoid IF [4]:

They are :

- Children under the age of 12 years

- Adolescents who are of normal weight

- Women who are pregnant or lactating

- Individuals with a history of an eating disorder

- Individuals with a BMI below 18.5 kg/m2

- Individuals over the age of 70 years

Conclusion

- Intermittent fasting seems to be gaining popularity all over the world, especially in the health-conscious community and also the medical community, and it seems, for the right reasons.

- There are multiple health benefits including weight loss, improvement of glycemic profiles, cardiometabolic parameters, cognition, neuroprotection, sleep and longevity. If implemented correctly, it seems to be a plausible replacement for people failing to achieve targets with daily caloric restriction.

- There remains scope for RCTs to assess long-term efficacy, and compare in detail the benefits of different types of IF, their effects in different populations (eg; type 1 and type 2 diabetes) etc.

- Having said that, it’s a method that dates back centuries across populations throughout the world and will remain because of deep-rooted reasons.

- As medical professionals, we need to understand the pros and cons, the do’s and don’ts of the method and advise our patients accordingly.

Click here to read the first part of this article- Intermittent Fasting: Introduction and Physiology: Part 1

Disclaimer- The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of M3 India.

About the author of this article: Dr Milind Jha, MD (General medicine), MRCP (UK) is a consultant physician from Darbhanga.

-

Exclusive Write-ups & Webinars by KOLs

-

Daily Quiz by specialty

-

Paid Market Research Surveys

-

Case discussions, News & Journals' summaries