Intermittent Fasting: Introduction and Physiology: Part 1

M3 India Newsdesk Apr 30, 2024

Fasting in various forms has been practised in various communities, mostly for religious grounds for centuries all over the world. This part of the article explains what is Intermittent Fasting (IF), along with its types and physiology.

Introduction

An American ecologist Jared Diamond said, “Agriculture was the worst mistake in the history of the human race”! Since our ancestors graduated from being hunter-gatherers to farmers, palaeolithic tools became more sophisticated and since we entered the industrial era, our biological history has witnessed rapid shifts. Modern life today is an embarrassment of riches and our bodies are unable to cope. Metabolically, most of the world has been in an era of surplus.

An abundance of sugar (glucose, fructose and fructose-rich corn syrup), processed food (refined carbs and fats) accompanied by an absence of physical activity, poor sleep and slower metabolism has put us amid the growing epidemic of metabolic diseases like obesity, diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular, and many other chronic musculoskeletal diseases. High body mass index (BMI) is also linked to some liver, and kidney diseases and cancers.

Despite the understanding that these are preventable diseases, we seem to keep failing to curb their rise. There have been many advances in the pharmacological avenues but recently there is growing interest in modifying dietary patterns. Various diets and exercise protocols have been explored and over the years, it's clear that no one size fits all.

The medical community has shown increasing interest in intermittent fasting (IF).

“To eat when you are sick, is to feed your illness”

- Hippocrates

Philip Paracelsus, the founder of toxicology and one of three fathers of modern Western medicine (along with Hippocrates and Galen) wrote, “Fasting is the greatest remedy—the physician within”. However, it is only recently that we have a more scientific understanding of the processes involved with fasting.

Calorie restriction and Intermittent Fasting: What's the difference?

Before entering into the discussion about intermittent fasting, it is important to understand the difference between caloric restriction and intermittent fasting. Calorie restriction (CR) is a reduction in total caloric intake that does not result in malnutrition.

This has been found to result in lower body weight and higher life expectancy in many species, including nonhuman primates. [1,5] Among overweight humans, short-term CR (6 months) has been shown to improve multiple cardiovascular risk factors, insulin sensitivity, and mitochondrial function.

Likely due to these physiological changes, clinical trials indicate CR may have several beneficial effects among overweight adults, in addition to weight loss. However, over the past several decades, obesity intervention trials have revealed that the vast majority of individuals find it difficult to sustain daily CR for extended periods. [1,5]

What is Intermittent Fasting (IF)?

Intermittent fasting, an eating pattern characterised by alternating periods of eating and fasting, has attracted significant attention in recent years due to its potential health benefits and extension of lifespan.[2]

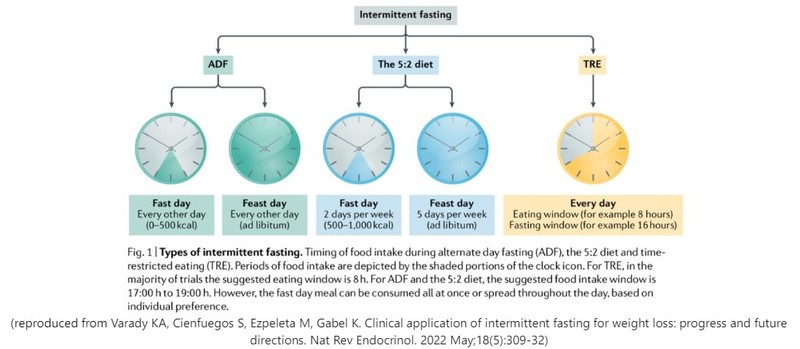

There are three popular types among others.[3,4,5,6]

- Alternate Day Fasting (ADF): Alternate days of zero-calorie fasting and unrestricted eating. Modified ADF (MADF) consists of alternate days of 0 to 40% or 0-600 Cal intake and unrestricted eating.

- Twice a week fasting (TWF): 2 days (consecutive or not) of 0 to 40% or 0-600 Cal intake and 5 days of unrestricted eating. The eating days are called “up” days and the fasting days are called “down” days. Described as the ratio of up and down days. TWF would be described as 5:2 IF.

- Time Restricted Eating (TWE): Involves fasting for 12-24 hours and the rest is the “eating window”. Described in the ratio of fasting: eating window times. For example, 16:8 IF means 16 hours of fasting and 8 hours of eating. (Ramadan fasts fall into TRE kind of fasting).

Other variations

- Variations of “up/down” methods - 4:3, 3:4, etc.

- Periodic fasting involves less frequent but longer periods of fasting eg; a 1–5 day pure water fast or a 4–7 day fasting simulated diet, designed to mimic the metabolic effects of fasting (the Navratri fast may be modified to fall into such category).

- B2 Regimen: 2 meals a day - breakfast at 6 AM, lunch at 2 PM, no dinner.

- One Meal a Day (OMAD) - a more severe form of IF. The caloric consumption happens in one meal. Although the same meal can be consumed over a few hours.

- Intermittent very low-calorie diet (VLCD) Therapy (not true IF as the subject consumes VLCD without fasting periods) - 1 day and 5 days per week VLCD.

Physiology of IF

- The fed and post-absorptive states are the only times relevant to normal eating routines whereas in the intermittent fasting regimen, an individual often cycles through the fed, postabsorptive, and fasting states.

- The health benefits of fasting result from “flipping the metabolic switch”, as described by Anton et al. [6]

- The onset of the metabolic switch is the point of negative energy balance at which liver glycogen stores are depleted and fatty acids are metabolised.

- This usually occurs beyond 12 hours after the cessation of food intake. The metabolic switch from utilising glucose to fatty acid-derived ketones represents an evolutionary trigger shifting metabolism from lipid/cholesterol synthesis and fat storage to the mobilisation of fat through fatty acid oxidation and fatty-acid-derived ketones, sustaining both muscle mass and function.

- Thus, it has been hypothesised that intermittent fasting regimens that induce this metabolic switch have the potential to improve body composition in overweight individuals. [5,6]

- Randle et al in 1963 proposed the “glucose-fatty acid cycle” theory of energy metabolism during feeding and fasting, in which glucose and fatty acids compete for oxidation. [7]

- The fed state, the post-absorptive state/early fasting state, the fasting state, and the starving or long-term fast state are the four stages of the fed-fast cycle.[8] Glucose is the primary source of energy after meals, and fat is stored as triglycerides in adipose tissue.

- During prolonged periods of fasting, triglycerides are mobilised and converted to fatty acids and glycerol. The liver then converts fatty acids to ketone bodies which become a major source of energy for many tissues during fasting state.

- Insulin is the main driver hormone in the feeding state, whereas in the fasting state glucagon is the primary hormone and the body uses liver stores of glycogen for energy.

- The onset of metabolic switch is the point of negative energy balance at which liver glycogen stores are depleted and fatty acids are metabolised which typically happens about 12h after cessation of food intake. [5,6].

- Metabolic switching through intermittent fasting results in improved metabolism, increased health span, longevity and reduced inflammation through multiple processes6,8.

- Pathways mediating these effects include rising AMP (and ADP) and lowered cellular ATP, resulting in the activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK)—ultimately inhibiting multiple anabolic pathways and stimulating autophagy, thereby removing damaged proteins and organelles, and improving mitochondrial function.

- A decrease in circulating amino acids and glucose inhibits mTOR and leads to decreased protein synthesis, and an increased mitochondrial biogenesis and autophagy—resulting in a prolonged life span in experimental models. [6]

- Reduced carbohydrate intake during fasting depletes liver glycogen, mobilises fatty acids from adipose tissues, and stimulates hepatic β-oxidation with a rise in ketone production (β -hydroxybutyrate).

- Additionally, the NAD+ deacetylase activity of sirtuins is activated, resulting in autophagy and reduced oxidative stress. Together, these pathways lead to longevity and improved health span. [6,8]

- Free fatty acids also activate the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPAR-α) and activate transcription factor 4 (ATF4), resulting in the manufacture and circulation of fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21), a protein with far-reaching effects on various cell types throughout the body and brain. [6,8]

- β -hydroxybutyrate also has signalling functions, including the activation of transcription factors cyclic AMP response element–binding protein (CREB) and nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) and the expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in neurons. [6,8]

Stay tuned for more...

Having discussed the basic physiology, there remains the effect of intermittent fasting on various hormones like insulin, including adipokines like leptin and adiponectin and their circadian rhythms. In the next part of the article, we will try to understand the effects of IF on various hormones, weight, cardiometabolic health, diabetes, metabolic syndrome cognition, mood etc.

We would also venture into how it remains different from various dieting forms and why it's difficult to sustain them for the long term. We would also discuss the so far available long-term data about the effects of IF from some umbrella reviews, meta-analyses and systematic reviews.

Disclaimer- The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of M3 India.

About the author of this article: Dr Milind Jha, MD (General medicine), MRCP (UK) is a consultant physician from Darbhanga.

-

Exclusive Write-ups & Webinars by KOLs

-

Daily Quiz by specialty

-

Paid Market Research Surveys

-

Case discussions, News & Journals' summaries