How to diagnose measles if you’ve never seen it before

M3 Global Newsdesk May 13, 2019

Summary

Measles- what began as a few cases in the US and Europe, has now become a global disease outbreak, largely perpetrated by the rise of anti-vaccine campaigns in these countries. Back home in India, about 3 million infants still could be at risk because of having missed the MMR vaccine, as per a UNICEF report.

In 2000, measles was declared eliminated in the United States. Since then, a whole generation of physicians has been practicing in the absence of this highly contagious respiratory illness. This begs the question: Could these physicians diagnose measles if they saw it? Could you?

“Most infectious disease physicians practicing today have never seen a case of measles. Most don’t even recognize it when they do see it; at first glance, it just looks similar to other viruses that cause fever and a rash,” infectious disease specialist Jeffrey Band, MD, Beaumont Hospital, Royal Oak, MI, told the Detroit Jewish News in a recent interview.

“However, measles is a very serious illness,” Dr. Band added. “It cannot be taken lightly.”

As of late April 2019, a total of 704 individual cases of measles have been confirmed in 22 states, according to the CDC. This year is on track to have the highest number of cases since the disease was declared eliminated in 2000.

Make a ‘rash’ decision

As Dr. Band said, measles looks similar to other viruses that cause fever and a rash. However, it does have some distinguishing symptoms. (Unfortunately, by the time symptoms appear, the patient has already been infectious for several days.)

In addition to a high fever (up to 105°F), measles is typified by a triad of cough, coryza (runny nose), and conjunctivitis—the “three Cs.”

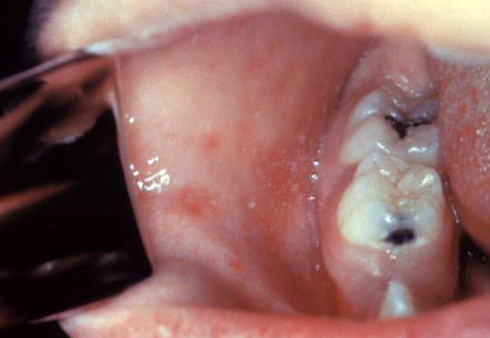

Two or three days after these symptoms begin, tiny white spots (Koplik spots) may appear inside the mouth. These spots are pathognomonic for measles.

Next, the characteristic rash breaks out, usually beginning as flat red spots appearing on the face at the hairline. “During the next 2 or 3 days, it descends to the trunk and then to the arms and legs,” explained Raymond A. Strikas, MD, MPH, of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, Atlanta, GA.

Fever frequently spikes when the rash appears.

“The rash is maculopapular and demonstrates coalescence, when the discrete macules combine into a larger red skin lesion,” Dr. Strikas added. “The rash is typically most intense on the head and upper chest, but is usually [also] present on the lower chest and arms.”

Consider patients to be contagious from 4 days before to 4 days after the rash appears.

Complications of measles may include diarrhea, ear infection, pneumonia and, rarely, encephalitis. People who are more likely to have complications include children younger than 5 years old, adults older than 20 years old, pregnant women, and immunocompromised individuals. (Notably, immunocompromised patients don’t always develop the rash.)

About 1 in 4 people who get measles will be hospitalized, according to the CDC. About 1 or 2 out of every 1,000 children with measles will die from respiratory or neurologic complications.

What to do

“If you suspect that someone has measles, you should obtain a blood sample for serology, and a nasopharyngeal specimen for viral isolation, and notify your local or state health department as soon as possible,” Dr. Strikas said. “Do not wait until lab tests come back. Control measures must be started immediately, not a week or two later.”

People infected with the measles virus should be isolated for 4 days after they develop a rash—ideally in a single-patient airborne-infection isolation room, according to the CDC. All staff entering the room should wear a protective mask or respirator that’s effective against airborne transmission.

There is no treatment available for measles, but supportive care can help relieve symptoms and decrease complications.

Children with a severe case of measles, however, should be treated with high doses of vitamin A, which should be given immediately upon diagnosis and again the next day, the CDC advises. The recommended age-specific daily doses are 50,000 IU for infants younger than 6 months of age, 100,000 IU for infants aged 6-11 months, and 200,000 IU for children aged 1 year and older.

Barring severe cases, patients normally improve 3 or 4 days after the rash begins. The fever subsides and the rash fades as it appeared, from the head downward. By 7-10 days after disease onset, patients are usually fully recovered.

An active decision

Of course, the best weapon against measles is to be vaccinated against it beforehand.

“Except for people who cannot be immunized or who had a previous severe reaction to [a measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine], I cannot think of a single reason not to immunize,” said Dr. Band.

“Some people seem to think that not vaccinating is a passive choice,” he added. “I disagree; not immunizing is an active decision to remain susceptible to serious diseases.”

This story is contributed by John Murphy and is a part of our Global Content Initiative, where we feature selected stories from our Global network which we believe would be most useful and informative to our doctor members.

-

Exclusive Write-ups & Webinars by KOLs

-

Daily Quiz by specialty

-

Paid Market Research Surveys

-

Case discussions, News & Journals' summaries