Epilepsy case studies: Dr. Srikant Jawalkar

M3 India Newsdesk Jan 05, 2020

In this two-part series, Dr. Srikant Jawalkar covers the gamut of epilepsy and seizures, explaining in depth the classification and diagnosis, and the difference between the two with the help of case studies.

Epilepsy, a very common neurological disorder is very easy to diagnose and treat, provided a proper history and clinical examination is done and the appropriate drug is chosen. Here is a brief discussion about diagnosis of epileptic disorders.

Classification of epilepsy

Epilepsy is a nomenclature given to a group of diseases whose common hallmark is seizures. The seizures themselves may present in myriad ways. The condition can be classified depending on:

- the nature of seizures experienced by the patient

- the underlying cause of seizures

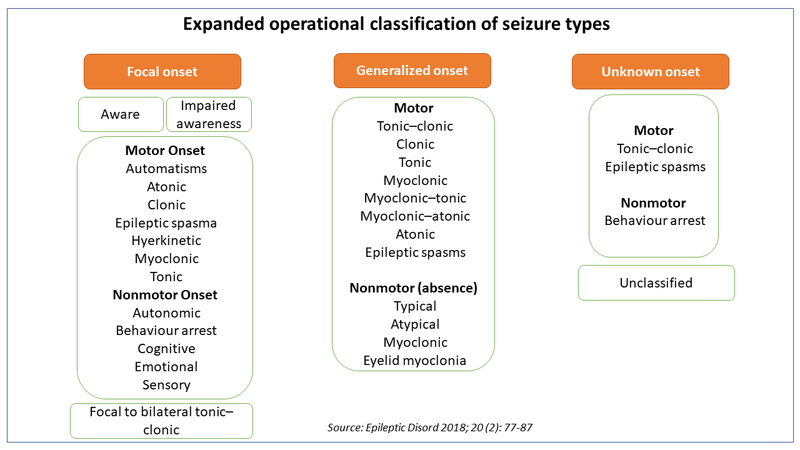

The 2017 classification proposed by ILAE (International league against epilepsy) classifies seizures based on the nature of onset,ie focal or generalized and whether the patient is aware (conscious)of surroundings during the seizure episode.

Epilepsy can also be classified depending on the underlying cause

- Primary or idiopathic or genetic: In this type, the age of onset is in childhood or young adulthood. The family history is positive for seizures and physical examination is often normal.

- Secondary or symptomatic: In this type, there is an underlying cause which is responsible for epilepsy. The cause may be:

- Structural like trauma, tumour, haemorrhage or infarct, arteriovenous malformation or congenital malformation, encephalitis, meningitis, cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, etc.

- Metabolic like hypo- or hyperglycemia, uremia, hepatic encephalopathy, etc.

- Toxic like alcohol (excess or withdrawal), drug overdose

Secondary or symptomatic seizures are often associated with symptoms and signs which suggest the underlying disease responsible for the seizures. A neurological examination may be abnormal.

It is very important to identify the type of seizure because the seizure type helps to identify the aetiology, eg. Idiopathic or primary seizures are often generalised in nature, whereas a focal onset of seizure suggests a structural cerebral defect like tumour or stroke, etc.

Secondly, the choice of a particular drug for treating epilepsy also depends upon the nature of seizures experienced by the patient. We will come to the choice of drug in the next section when we take up the treatment of epilepsy.

Establishing a diagnosis

Diagnosis of epilepsy can be divided under two subheadings:

- Deciding what the patient has is really epileptic seizure or not

- If yes, what is causing the seizures?

The diagnosis is often clinical and in most instances based on the history given by the patient and eyewitnesses who saw the seizures. The patient can give information about aura or premonitory symptom which he/she experiences before losing consciousness.

Diagnosis is relatively straight forward in case of convulsive motor seizures where the involuntary movements can be seen by the observer. These may be:

- focal, i.e. restricted to face or a limb or one half of the body, OR

- generalised when the entire body convulses. Sometimes a focal seizure can get secondarily generalised

The patient loses consciousness (awareness according to 2017 ILAE classification). Non-motor seizures are more difficult to diagnose because they may present with varied symptoms. Sometimes, the symptoms are so bizarre that they are not recognised as seizures. Such people often go to a psychiatrist or the symptom is passed off as insignificant.

Case 1

A 7-year-old child brought by parents saying that the teacher complains that the child is inattentive in the classroom. Parents also noticed that he sometimes suspends whatever activity he is doing and stares, apparently lost in thoughts. This lasts only a few moments and the child immediately resumes whatever he is doing. This is a typical story of absence seizures (earlier called Petit mal). It typically occurs during the school going age.

Case 2

A 17-year old girl complains that things fall from her hands because she gets sudden jerks in her limbs, especially on waking up. Once in a while she also gets a major (tonic-clonic generalised) seizure. The girl has Juvenile Myoclonic Epilepsy (JME). Patients with myoclonic seizures complain of objects falling from their hands due to sudden jerky movements of hands or frequent falls if legs or trunk is affected. Myoclonus often occurs after waking from sleep.

Case 3

A 34-year old man, a lecturer in a college suddenly becomes unaware of his surroundings. He can continue to teach but after a few minutes when he comes back to his senses he cannot recollect what happened. Sometimes he makes chewing and smacking movements with his lips and spits in the class during such episodes. This is very embarrassing later, but he has no control over the automatisms because he is unaware of the events.

This man has atypical absence seizures (also called complex absence or temporal lobe or antiepileptic seizures). These seizures often last longer than other types of seizures. These patients often consult psychiatrists or exorcists before coming to the neurologist.

The above cases are some of the unusual ways in which seizures present. Their diagnosis is missed because:

- the patient and relatives do not recognise them as seizures

- the doctor is not aware of these common but unusual presentations

Syncope and hysterical conversion reaction sometimes masquerade as a seizure

Elicitation of circumstances in which the episodes occur, the absence of frothing at mouth and tongue bite or injury during the attacks help distinguish them from GTCS (generalized tonic-clonic seizure).

Investigation

Once it is ascertained that the patient has an epileptic seizure the next step is to find out the underlying cause, i.e. primary/idiopathic or secondary/symptomatic epilepsy. As mentioned above, history and physical examination help to distinguish between the two. However, sometimes help of investigations is needed.

- A word of caution at the outset, normal investigation reports do not negate the diagnosis of epilepsy. Your clinical acumen is the ultimate tool to diagnose epilepsy.

- An EEG helps in two ways:

- Firstly the presence of epileptic discharges confirms the diagnosis of epilepsy, particularly in those cases with unusual seizure types

- Secondly the nature of epileptic discharges helps to categorise epilepsy which in turn helps to decide the choice of antiepileptic drug and long term prognosis

- Imaging like CT scan or MRI brain primarily help to rule out/in secondary epilepsy.

- Blood tests may be needed to exclude metabolic/toxic causes.

Another word of caution- a single seizure provoked by an easily treatable cause like hypo- or hyperglycaemia, eclampsia, etc. does not require prolonged treatment with an anti-epileptic drug.

Stay tuned for the next article in the series that discusses the treatment of epilepsy.

Disclaimer- The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author's and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of M3 India.

The writer, Dr. Srikant Jawalkar is a Senior Neurologist with over four decades of experience in the field.

This article was originaly published on 20.03.19

-

Exclusive Write-ups & Webinars by KOLs

-

Daily Quiz by specialty

-

Paid Market Research Surveys

-

Case discussions, News & Journals' summaries