Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Protocols

M3 India Newsdesk Jul 09, 2024

This article explains the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) pathways, which use multimodal, multidisciplinary approaches to reduce postoperative complications and hospital stays while improving patient outcomes and satisfaction.

In 1990, to reduce ICU stay in cardiac surgery patients, fast-track surgery principles were laid. Kehlet and Mogensen proposed a novel multimodal approach to perioperative care resulting in reduced hospital stay following colectomy.

ERAS society was formed later to disseminate and implement enhanced recovery best practices globally and they introduced enhanced recovery programme (ERP) principles which have been successfully applied across the surgical spectrum.

ERP principles aid in the integration of evidence-based, multimodal, multidisciplinary interventions that mitigate the undesirable effects of the surgical stress response. Implementation of ERAS pathways has the potential to limit this variability and improve patient safety.

Perioperative care pathways reduce postoperative complications and shorten hospital length of stay without increasing post-discharge readmission rates. This led to the migration of some surgical procedures from the inpatient setting to the outpatient setting.

The ultimate aim of ERAS pathways is to improve patient-reported outcomes, including return to activities of daily living, and to address psychosocial issues (e.g., anxiety, depression, cognitive dysfunction) and enhance patient satisfaction.

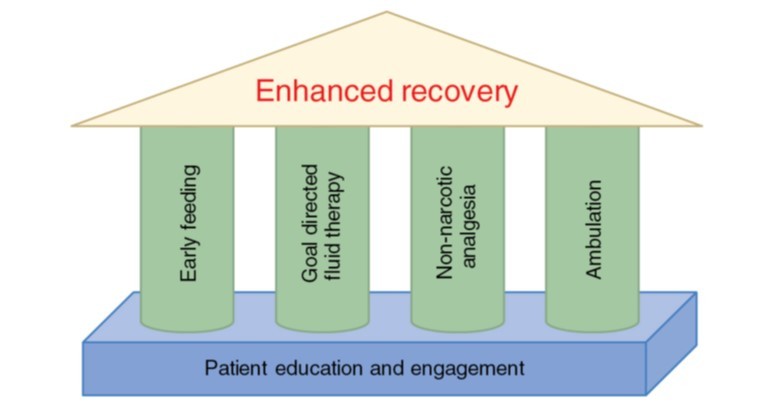

4 pillars of ERP

Fundamental surgical principles, such as thromboembolic prophylaxis, prophylactic antibiotics, appropriate application of minimally invasive approaches, and minimisation of drains/lines/tubes are critical to ERPs. In addition, modern ERP approaches consist of effective patient education and engagement, upon which stand “4 pillars” of enhanced recovery:

- Early postoperative feeding

- Goal-directed fluid therapy

- Opioid-sparing analgesia,

- Early ambulation

These events occur at different phases in a surgical patient spectrum of care.

The foundation of all ERPs, patient engagement and education, is of critical importance. Good pre- and post-rehabilitation education for the patient and caregiver(s) enables a "team approach" that will result in better and more favourable outcomes.

Figure 1: The “4 pillars” and foundation of enhanced recovery programs (ERPs).

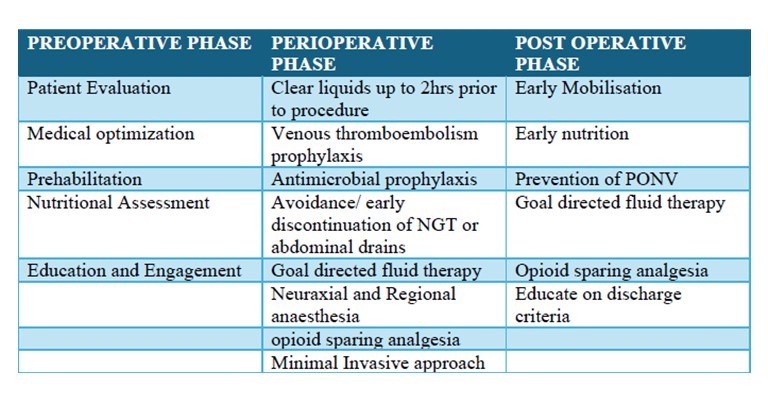

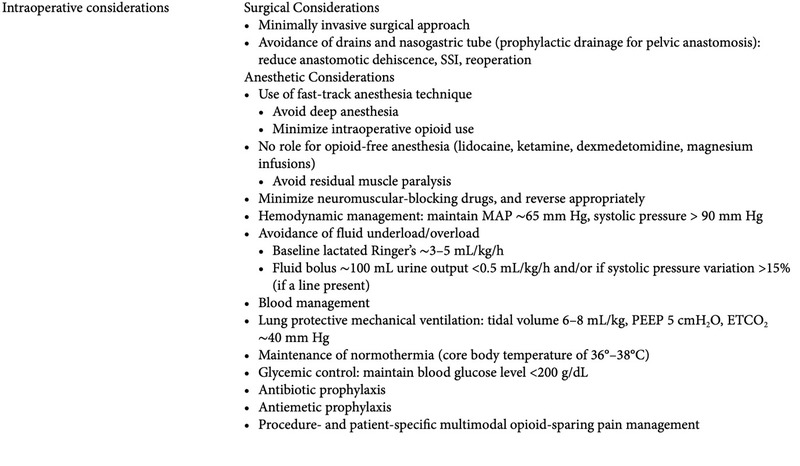

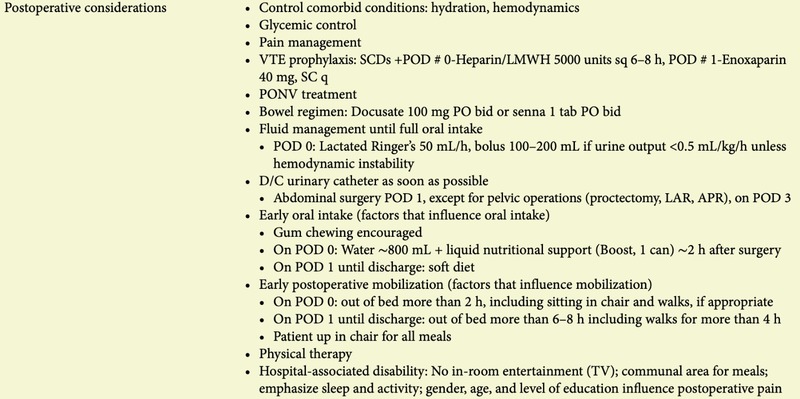

ERAS pathways typically include 15-20 interventions divided over three phases viz., preoperative phase, perioperative phase & postoperative phase. Essential elements are listed in table 1.

Table 1: Essential elements of ERP

NGT- nasogastric tube. PONV- postoperative nausea vomiting.

Components of the ERAS pathway

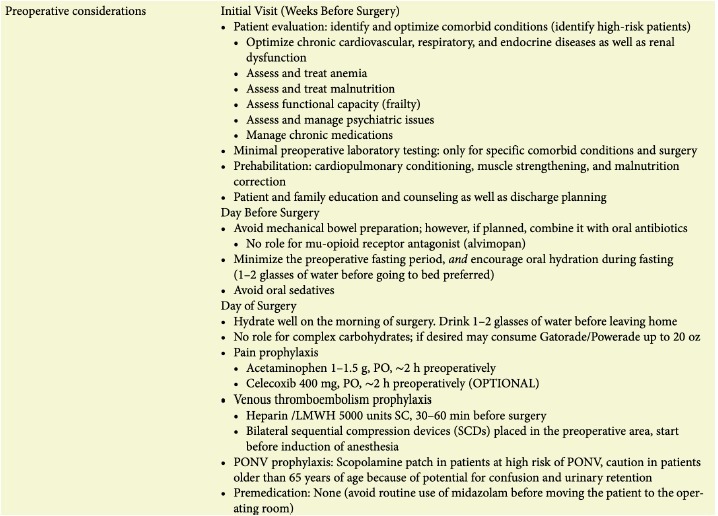

Preoperative phase:

1 . Risk assessment and optimisation of comorbid conditions as well as risk stratification. Preexisting comorbidities determine postoperative outcomes. Hence preoperative identification and optimisation with specific interventions modify perioperative care which forms a crux of risk stratification. Modern preoperative clinics promote global optimisation through patient engagement and interdisciplinary collaboration between preoperative anaesthesia and surgical teams to achieve shared decision-making and better compliance with ERAS components

2. Prehabilitation:

Prehabilitation is a paradigm shift in preoperative care, which includes cardiopulmonary conditioning, muscle strengthening, and malnutrition correction. Prehabilitation reduces frailty improves postoperative functional status and shortens hospital stay. It allows

patients to become engaged in their care.

3. Patient and family education and counselling:

Involving patients in surgery decisions improves recovery by reducing anxiety and promoting participation in care. To improve patient engagement:

- Provide educational materials on surgery approaches, pain control, diet, and ambulation in a clear and understandable format.

- Clearly explain the goals of the program and the reasons behind care decisions.

- Encourage patient participation by emphasising the importance of their role in recovery.

- Set realistic expectations about the recovery process.

Perioperative phase:

This includes events in and around the operative phase.

- Minimal fasting prior to surgery and sufficient fluids during the fast. Current guidelines recommend for clear liquids up to 2 hours and solid food 6 hours before general anaesthesia if there are no concerns for gastroduodenal functional impairment.

- According to recent meta-analyses, there are no advantages to preoperative carbohydrate loading over placebo in terms of the rate of postoperative complications and length of hospital stay.

- Avoidance of mechanical bowel preparation: Avoidance of mechanical bowel preparation in patients undergoing colonic surgery has been recommended for enhanced recovery after surgery. The routine use of preoperative mechanical bowel preparation is not recommended in colonic surgery except, based on limited evidence, for patients undergoing an anterior resection with a diverting stoma.

- Antibiotic prophylaxis: The antimicrobial agent should be started within 60 minutes before surgical incision. Although single-dose prophylaxis is usually sufficient, the duration of prophylaxis for all procedures should be <24 hours. Unless there is suspicion of ongoing infection, continuation of antibiotic is discouraged beyond 24 hrs of surgery.

- Venous thromboembolism(VTE) prophylaxis: Mechanical prophylaxis alone may be appropriate in patients with high bleeding risk, while a combination of mechanical and pharmacologic prophylaxis is preferable in patients with high VTE risk.

- Surgical considerations: Minimally invasive surgical approach wherever possible. Avoid unnecessary usage of drains and nasogastric tubes.

- Anaesthetic considerations: Fast-track anaesthesia aims for quick recovery by using minimal drugs and avoiding long-lasting effects. This can lower hospital readmissions. Avoid deep anaesthesia. Minimise opioid use. Avoid residual muscle paralysis. Minimise neuromuscular blocking drugs and reverse them appropriately. Mechanical ventilation includes lung protective strategies such as tidal volume 6–8 mL/kg, PEEP 5 cmH2O, ETCO2∼40 mm Hg.

- Goal-directed fluid therapy and hemodynamic management: ERAS principles manage fluids differently than traditional care. They focus on minimal fluid loss during surgery and encourage pre- and post-operative hydration. "Zero balance" is the goal, with baseline fluids and blood replacement as needed. Hemodynamic management aims for good blood flow and organ function using fluids, blood, and medications. Cardiac output monitoring is required for high-risk patients undergoing major surgery with expected significant blood loss(>1L blood loss).

Postoperative phase:

1. Early oral nutrition

Early resumption of oral nutrition helps recovery while the presence of nasogastric tubes, ileus, severe shock, intestinal ischemia, or a high-output fistula may preclude oral nutrition and necessitate other forms of support

(i.e., parenteral supplementation).

2. Early mobilisation

Early mobilisation improves pulmonary and gastrointestinal function, reduces VTE, and avoids loss of muscle mass and function. Furthermore, unimpaired muscle function is essential for hospital discharge and return to activities of daily living. Patient co-operation

and early consultation with physical therapists are imperative for the effective implementation of this component of the ERAS pathway

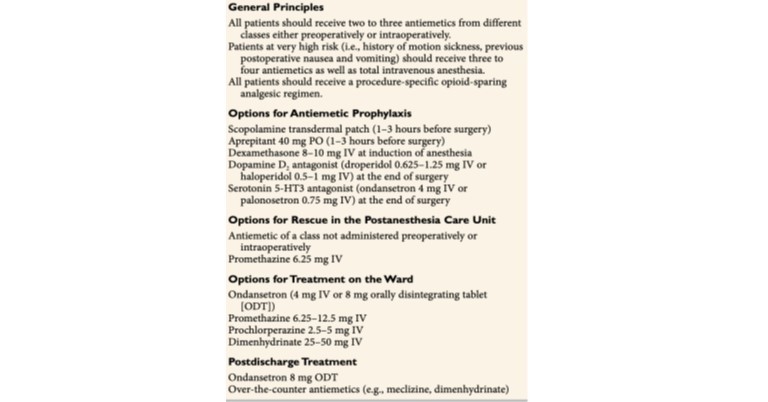

3. Nausea and vomiting prophylaxis

Nausea and vomiting after surgery (PONV) slows recovery. All patients should receive at least 2 to 3 antiemetics from different classes, either preoperatively or intraoperatively. Patients at very high risk (e.g., history of motion sickness, history of previous PONV, high

opioid requirements after surgery) should receive 3 to 4 antiemetics. Recommendations for

PONV management is depicted in the following table:

Table 2. Recommendations for the management of postoperative nausea and vomiting

4. Procedure-specific pain management

Focus on getting patients moving, not just pain scores. Use multimodal analgesia to avoid opioid side effects. Neuraxial blocks are used less often due to mobility concerns. At home, use NSAIDs round the clock in the early days and take opioids when necessary. Other options like ice, elevation, and relaxation techniques can also help manage pain.

Table 3. Multimodal analgesia and opioid sparing analgesia strategies

Following is the sample ERAS pathway depicting the sequence of events starting from the initial visit to discharge following surgery in a standardised manner.

Disclaimer- The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of M3 India.

About the author of this article: Katakam Sai Krishna is MS, MCh GI SURGERY (SGPGI) working as an Assistant professor in Surgical Gastroenterology, KGMU Lucknow.

-

Exclusive Write-ups & Webinars by KOLs

-

Daily Quiz by specialty

-

Paid Market Research Surveys

-

Case discussions, News & Journals' summaries