Case 2: A delicate sound of thunder: Diagnosis clinched; what's next?- Part 3

M3 India Newsdesk Dec 19, 2020

Ready for a new part of the case challenge? Here, Prof. Dr. Sundeep Mishra reveals further details and the eventual diagnosis made with a detailed evaluation of your responses from the second part.

Study this next stage case and answer the questions in the boxes below. Get your responses evaluated from the expert. Our expert will share comments as the case progresses. Stay tuned!

Click to read other articles from Dr. Sundeep Mishra.

Summary

An elderly lady, known case of COAD and hypertension, presented with symptoms of severe chest tightness, breathlessness and sweating with near-past H/O of unwellness and ↓mobility. Vital parameters with hypotension, tachycardia, tachypnoea suggested possibility of shock probably of cardiac origin.

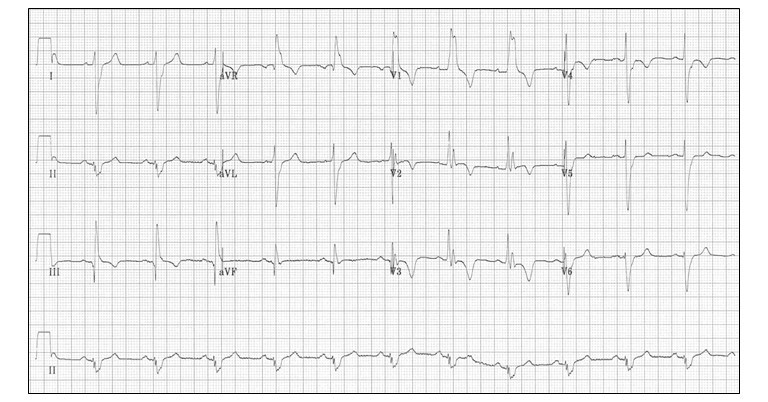

ECG showed sinus tachycardia with ST- T changes and possible ST elevation in III and aVF

X-ray showed no cardiomegaly or pleural effusion but possible patchy areas of consolidation. Lab values revealed ↑Hb (18.2,) and some leucocytosis. ABG suggested mild respiratory acidosis. hsTroponin T was elevated. Simplified Geneva score for PTE was 3 but d-dimer was at border-line.

A most likely diagnosis of ACS/AMI was entertained and the patient was planned for angiography ± angioplasty. However, while waiting for the COVID test (before undertaking the invasive procedure), the patient suddenly collapsed, became unconscious with an idioventricular rhythm of 40/min with no pulse or blood pressure recorded. Cardiac arrest with pulseless electrical activity followed.

Following the aseptic precautions mandated in a COVID patient and with full protective personal equipment for the health-care workers, the patient was intubated and standard cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) was initiated. There was a return of spontaneous circulation but blood pressure was in the range of 80-90 systolic; the total CPR duration was >1 hour. Bedside echocardiography revealed diffuse hypokinesis, with left- and right-sided ventricular dilatation with LV ejection fraction of 25%.

The patient was immediately rushed to cath lab with two teams at work simultaneously; coronary angiogram being performed from right groin and intra-aortic balloon pump support instituted from the left groin. However, the coronary angiogram showed no obstructive lesions in the coronary artery.

Discussion on answers to questions

Question 1: What is the likely diagnosis now?

Acute myocardial infarction

Interestingly, nearly 1 in 4 respondents still felt that AMI was the most likely diagnosis but with various associated complications; ventricular arrhythmias (tachyarrhythmnias, CHB) or heart failure or ventricular aneurysm etc. As per the monitor, there were no rhythm abnormalities during the entire course of the procedure, so arrhythmia as the prime cause seems very unlikely. Likewise developing heart failure so fast especially in context of normal coronary is not possible. Finally, developing ventricular aneurysm with just 30 minutes of chest pain and no past history of CAD is also very unlikely. Moreover, X-ray or echo did not show any evidence of aneurysm.

While 15% AMI cases can have non-obstructive anatomy (maybe distal small vessel disease), in this case even clinical diagnosis of AMI is itself not well established. On closer analysis ECG is not diagnostic; rather it possibility rules out ACS. Negative T waves in leads III and V1 can be seen but in practice, they are very uncommon in a case of ACS (observed in only 1% of patients with ACS).

Troponins can be elevated in other conditions also. With normal coronary anatomy, at this stage diagnosis of AMI seems very unlikely and does warrant considerations of other possibilities.

Myocarditis probably related to COVID infection

One in 5 participants suggested myocarditis ± COVID infection as the most likely diagnosis. However, rather sudden onset of the whole disease with no prodrome of viral infection makes this diagnosis unlikely.

Pulmonary thrombo-embolism – 20% of respondents felt that this was the most likely diagnosis

Presenting symptoms are compatible with diagnosis of PTE. Elderly status (risk factor for PTE) and H/O of immobilisation (risk factor for PTE) is also present. Obstructive shock can happen with massive PTE.

ECG reveals sinus tachycardia and non-specific ST-T wave changes. However, closer examination reveals additional findings favouring PTE. Negative T waves in leads III and V1 as observed here occur in 88% of patients with acute PE (versus in only 1% of patients with ACS) and this point can be used to differentiate it from a coronary event.

X-Ray is another simple test which should have been more closely examined.

While there is no cardiomegaly or pleural effusion, on closer look several signs suggestive of pulmonary embolism are present;

- Hampton’s hump; wedge-shaped, pleural-based consolidation seems present

- Westermark sign; oligemia in right lower lung field is present

- Fleischner sign; central pulmonary artery seems prominent

ABG suggestive of mild respiratory acidosis could be a consequence of pulmonary infarcts. Troponin T can be elevated with PTE. D-dimer test is borderline. However, D-dimer test has a negative predictive value only in case of low probability of PTE. In this case however, several findings; clinical, shock, ECG, X-ray are fitting into the diagnosis of PTE making the probability high and not low. Moreover, the Simplified Geneva Score is 3 making it high possibility of PTE.

Echocardiography reveals evidence of right-sided ventricular dilatation which fits into the diagnosis of PTE although reduced LV function with LV ejection fraction of 25% is a bit odd, probably explained by prolonged CPR.

Pneumonia/ARDS± COVID Infection

15% of the respondents continued to entertain a possibility of COVID lung disease but as already discussed, several clinical factors and lab findings as below are against this diagnosis.

- Clinical findings- Sudden onset of disease (possible if pneumonia was less symptomatic but suddenly ARDS set in), symptom of chest tightness, no cough.

- Vital parameters and general examination- Suggests shock, likely cardiac origin; nconsistent with diagnosis because shock seems cardiac not septic (cold clammy skin). Cardiac origin shock is a rather late event in pneumonitis and develops only in full-fledged respiratory failure.

- ECG- Sinus tachycardia, ? ST elevation in III and aVF, T-wave inversions in the anterior (V1-4) and inferior leads (II, III, aVF). ECG is not fitting into diagnosis of pneumonia/respiratory failure.

- X-ray chest PA view- No cardiomegaly, no pleural effusion, and possible areas of patchy consolidation. Generally one would expect a more gross derangement in pulmonary parenchyma.

- ABG- It is suggestive of mild respiratory acidosis. This finding actually does not fit into the diagnosis because with this kind of clinical picture, particularly shock, we would have expected a more gross derangement of ABG.

- Echocardiography with bi-ventricular dysfunction suggests a prominent cardiac involvement even if secondary to respiratory system. Such gross derangement of cardiac function is very unlikely with just pneumonia.

Thus, considering everything, pneumonitis/ARDS as the primary cause is practically ruled out.

How to confirm the diagnosis

On the balance of things, PTE seems the most likely diagnosis now, but how to rule it in or rule out? Meanwhile, the patient turned out COVID negative. Laboratory evaluation revealed the total creatine phosphor-kinase (CPK) level to be 430 U/L, CPK-MB level at 9.5 mg/mL.

Ventilation–Perfusion scan (V/Q scan): None of the respondents asked for a V/Q scan at this stage. While traditionally, ventilation-perfusion scanning has been a key part of the diagnostic strategy in patients with suspected PE, it does not provide a definitive answer about the presence or absence of PE in up to 80% of patients. However, when the use of contrast dye is contraindicated, ventilation-perfusion scanning may be the diagnostic test of choice.

We performed the V/Q scan and it revealed a high-probability scan. PIOPED study has revealed that a high-probability scan result had a positive predictive value of 88%, but in view of high pre-test probability of PTE, this test is almost diagnostic of PTE in our case.

Pulmonary angiography: 5% of our respondents suggested pulmonary angiography to be performed. While pulmonary angiography is considered the gold standard in the diagnosis of PE, physicians infrequently order it versus other non-invasive tests like V/Q scan or Helical CT. Reasons for this under-use could be due its invasive nature, high cost and limited availability of the test. However, in today’s practice, pulmonary angiography might be considered if the results of the CT study are inadequate and the suspicion for PE is still high.

In our case, however, the patient was already on the cath table (post normal coronary angiogram) and it would have been rather simple to do a pulmonary angiogram to clinch the diagnosis, but at that point, the treating physician was so fixed on diagnosis of CAD, ACS that no other possibility was thought of.

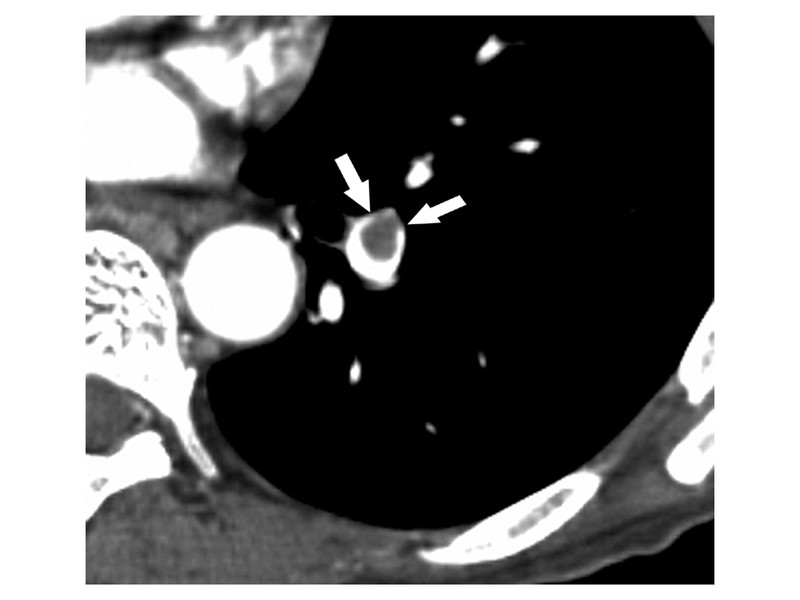

MDCT: Nearly 1 in 4 respondents suggested computed tomographic pulmonary angiography (CTPA) as the main diagnostic test.

Nowadays, CTPA has become the imaging procedure of choice in patients with suspected PE. Compared with V/Q scans, CTPA has several advantages:

- ▲ diagnostic accuracy

- Ability to provide a clear test result (either +ve or –ve i.e. rule in or rule out PE)

- Faster acquisition time with high-contrast images

- ▲ availability

- Can suggest alternate diagnosis as well, such as pneumonia, ARDS, COAD, structural defects in the heart and lungs etc.

PIOPED II investigators reported MD-CTPA to have a sensitivity of 83% and a specificity of 96% for diagnosing PE. In clinical practice, if the clinical suspicion is moderate to high (as in our case), CTPA is an appropriate initial diagnostic method.

CT scan demonstrates a pulmonary embolus that results in an eccentrically positioned partial filling defect, which is surrounded by contrast material and forms acute angles with the arterial wall (arrows).

Discussion

Pulmonary embolism is one of the most common cardiovascular diseases (with an estimated annual incidence as high as 1/1000) and one of the most common causes of mortality (including sudden cardiac death) as well. The clinical presentation of patients with PE is highly variable and forms a wide spectrum, ranging from asymptomatic to those presenting with shock (obstructive). The non-specificity of signs and symptoms make recognising this disease in first go a bit challenging, even among experienced physicians. It is estimated that 1 in 6 patients with PE are diagnosed after a delay of more than 10 days from the onset of symptoms. PE if left untreated can be fatal in 30% of the patients versus <5% when treated. Timely diagnosis is of vital importance.

In our case, the clinical image of a pulmonary embolism was ambiguous, making it difficult to propose an exact diagnosis at an early stage. Moreover, presences of possible ST-segment elevation, a positive Troponin T test and –ve D-dimer test mislead us till coronary angiogram was done. Clinical probability score (Simplified Geneva Score of 3) should have alerted us right from the beginning the possibility of acute PE and combined with the ECG finding of negative T wave in lead III and V1 and X-ray signs like Hampton’s hump, Westermark sign and Fleischner sign along with echocardiographic appearance of RV dilatation should have clinched the diagnosis.

These probability rules are highly effective in determining the pre-test probability of PE, which is the crucial step in the diagnostic approach before the selection of further diagnostic tests. PE can be ruled out only when clinical probability is low and there is a normal D-dimer result. However, D-dimer testing is not suitable to be used in patients with a high clinical probability and should not be used as a PE screening test. Moreover, in older patients (like ours) with a suspicion of PE, the specificity of the conventional D-dimer threshold might be too low to render this approach successful in clinical practice. Also, D-dimer tests should be used with caution in patients with symptoms lasting more than 14 days, and patients receiving therapeutic heparin treatment or oral anticoagulant therapy. MD-CTPA has considerably advanced the radiological visualisation of PE and its accuracy has been demonstrated to be robust enough to serve as single imaging test for PE. As a result, this technique is now practically an investigation of choice at least in high-risk subsets.

What next?

This is a special, real-life case challenge series. Send in your responses latest by December 22 (Tuesday).

Stay tuned for the next part which will cover the next stage of the case and the expert's discussion of the answers to the questions posted above.

Disclaimer- The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author's and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of M3 India.

The author, Dr. Sundeep Mishra is a Professor of Cardiology.

-

Exclusive Write-ups & Webinars by KOLs

-

Daily Quiz by specialty

-

Paid Market Research Surveys

-

Case discussions, News & Journals' summaries