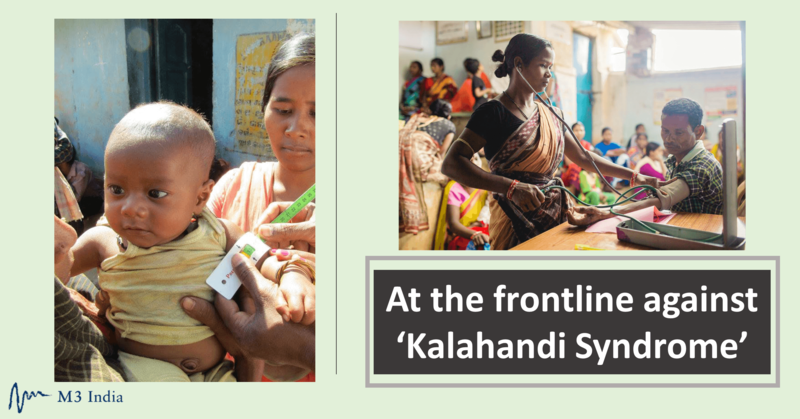

At the frontline against 'Kalahandi syndrome'

M3 India Newsdesk Sep 10, 2019

“Kaki aap apne TB ka ilaaz toh kara rahi hai na?... Ab sarkaari aspataal mein TB ka ilaaz bilkul muft mein karaiye…,” goes a radio ad by the Ministry of Health and Ministry of Women and Child Development that urges listeners to get a free TB checkup at their local government hospitals. But like many government policies, which are exceptional just on paper, especially in Kalahandi, one of the remotest and under-developed parts of India, with dismal health and nutrition indicators, the region has become infamous among social workers who coined the term ‘Kalahandi syndrome’.

Here, more than anywhere, doctors are hard to come by, making it difficult to enforce even the basic health goals in the far-flung villages and remote hamlets. In a country that has a doctor-patient ratio of 1: 10,189, against the WHO-recommended 1:1,000, the availability of doctors per capita is even more skewed in rural India. “The clinics/Primary Healthcare Centres (PHCs) in the rural regions are not well-equipped,” says a doctor, pursuing his post-graduation in a Pune-based hospital. “We merely end up being referral doctors since there is no infrastructure to treat advanced illnesses and patients more often than not have to be sent to city hospitals for treatment,” said the doctor who has briefly worked in the Vasind village of Thane district.

This is one of the main complaints of doctors who are considering rural postings. Since their training is mostly geared towards working in multi-speciality hospitals with state-of-the-art equipment, most of them balk at the thought of working in run-down government primary healthcare centres with practically no infrastructure and untrained staff. Dr Sandeep Praharsha, who has worked in many villages in Odisha, said that the Indian-educated doctors are unprepared for the challenges of the rural healthcare ecosystem.

“We must first strengthen the healthcare system in our villages before we can compel MBBS graduates to go for their rural postings,” added Dr. Prakash Marathe, ex-president of the Indian Medical Association's Pune wing. While he agreed that rural postings are necessary, they “become difficult to pursue given the lack of basic facilities and logistics in these places.”

Dr. Marathe, however, says that rural postings will seem more lucrative to doctors if they are made more flexible in terms of granting them based on the doctors’ specialisation preference, while making the “social environment more favourable for them to work.” Dr. Tushar Garg, who has been working with Innovators in Health (IIH) in Dalsing Sarai of Bihar’s Samastipur district since 2015, questions that stand though by blaming medical associations for not taking up these issues. “While they stand for doctors’ rights, which they definitely must, why not stand for improving the rural healthcare infrastructure,” he insists, while pointing to the vicious cycle of the sorry state in which rural healthcare currently is.

Dr. Marathe and Dr. Praharsha also pointed to the length of medical education which could also be a deterrent for students. After giving it close to 10-12 years of your life, practising in villages doesn’t seem too lucrative to most doctors. What then made Dr. Praharsha and Dr. Garg to take the leap? “During my masters in the UK, I got the opportunity to volunteer in a non-profit organisation working in policy, advocacy, and solidarity for refugees and asylum seekers. It made me realise how privileged I was. I felt that the humanitarian sector was my calling,” answers Dr. Prahrasha.

“But what about the taxpayers’ money that sponsored your education?” questions Dr Garg. "When my education is sponsored by the government, why do I not give back to my people?” the humble doctor asserts.

A recent bill enabled the formation of the new National Medical Commission while disbanding the Indian Medical Council. But Dr. Prasharsha believes, “the only positive aspect of the new bill is giving license to mid-level healthcare practitioners like ANMs (Auxiliary Nurse Midwives) in PHCs.” This, he believes, can help provide care for basic ailments and some minor operational procedures in rural areas. The other expectations doctors have from the new body are updating the medical curriculum where medical students are encouraged to participate in various village-level activities like VHNDs (Village Health Nutrition Days) and medical outreach camps, community level awareness and so forth. “Unless students are exposed to the grassroots level problems of rural primary healthcare, they’re not going to care about these,” insists Dr. Praharsha.

Dr. Garg concludes saying, “Most doctors take up the profession wanting to serve people and improve the healthcare system. Isn’t working at the grassroots doing exactly that?”

The author, Vinaya Patil is a freelance writer and a member of 101Reporters.

-

Exclusive Write-ups & Webinars by KOLs

-

Daily Quiz by specialty

-

Paid Market Research Surveys

-

Case discussions, News & Journals' summaries