Article: Managing Multimorbidity and Polypharmacy in the Ageing Population

M3 India Newsdesk Apr 23, 2025

This article outlines a comprehensive approach to managing multimorbidity and polypharmacy in older adults, emphasising individualised care plans. It highlights the importance of aligning treatment strategies with patient goals to enhance quality of life and minimise medication-related risks.

As of 2025, older patients frequently contend with accumulating chronic conditions and expansive medication lists. These overlapping ailments and treatments can trigger conflicting regimens, adverse effects, and diminished quality of life.

The Multimorbidity Challenge

Multimorbidity, defined as having two or more chronic conditions, affects over 60% of individuals aged 65 and up, with prevalence climbing past 80% for those 85 and older. Each added condition among people aged 65 to 74 significantly increases healthcare demands and functional limitations (1.35 times for men and 1.62 times for women).

A broader, person-focused approach is needed, one that aligns treatment choices with each patient’s priorities while minimising burdens.

1. Clarifying Patient Goals and Preferences

Begin conversations by asking about the patient’s top concerns. Structured inquiries such as “What matters most?” serve as a foundation for setting acceptable treatment burdens and quality-of-life thresholds. Document care wishes and integrate advanced care planning so that treatment aligns with long-term objectives rather than numerical targets alone.

2. Comprehensive Assessment Protocols

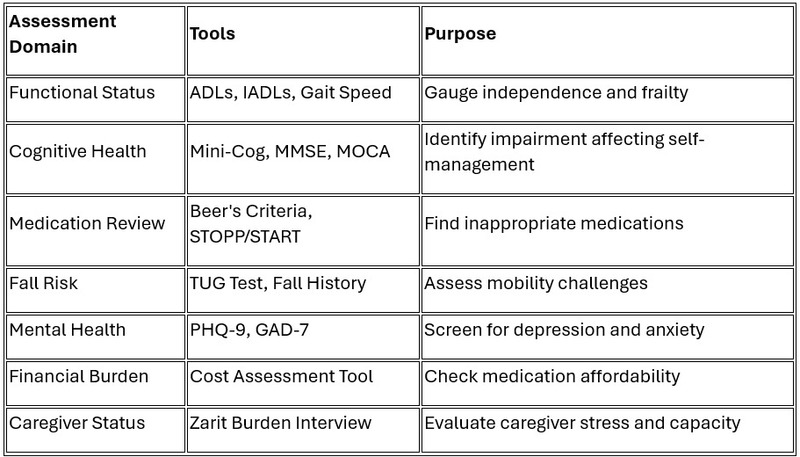

A thorough evaluation is essential:

Medication reviews must account for all prescriptions, over-the-counter drugs, and supplements, with attention to interactions and redundancies.

3. Developing Individualised Care Plans

Use findings from the comprehensive assessment to set priorities. Evaluate conditions by their impact on function, symptoms, and risk. Create hierarchies, tackle key conditions first, and set measurable goals with predetermined reassessment intervals. If a caregiver is involved, including them in written plans and documenting advance care directives can be helpful. The plan has to accept trade-offs between disease-specific treatment intensity and reducing overall burdens.

4. Simplifying Medication Regimens

Reducing medication complexity can lessen potential harm:

Medication Optimisation Checklist

- Confirm the necessity of each medication.

- Flag drugs listed as potentially inappropriate for older adults.

- Weigh risks and benefits based on life expectancy.

- Streamline dosing schedules for easier use.

- Deprescribe when drawbacks overshadow gains.

- Use adherence tools (pill organisers, blister packs).

- Combine compatible medications if possible.

- Address affordability challenges.

- Reassess high-risk prescriptions for older patients.

Research shows that simplifying regimens can cut adverse events by up to 30% and boost adherence.

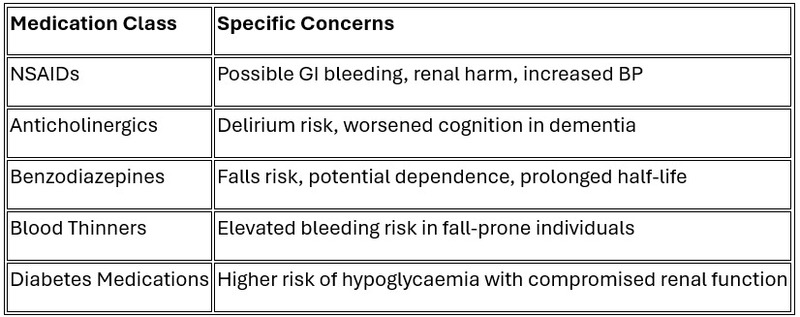

- High-Risk Requiring Caution

- Addressing Medication Cost Burden

High costs reduce adherence. India, till date, mostly spends out of pocket for health care expenses and therefore discussing the cost burden is very important. If required, low-cost alternatives should be looked for wherever possible, and very high-cost newer medications with questionable benefits might have to be avoided altogether.

5. Coordinating Interdisciplinary Care

Team-based care benefits adults with complex needs. Assigning clear roles to all providers, maintaining open communication (especially around care transitions), and considering a care coordinator may be helpful.

- Caregiver Support

Caregivers are vital. Assess their capacity, provide training in medication oversight and share important documents with their permission. Data suggests caregiver involvement can improve adherence by up to one-third.

6. Promoting Therapeutic Lifestyle Modifications

Non-pharmacological tactics can be very effective. Recommend individualised exercise routines that account for physical limitations, suggest Mediterranean or DASH eating habits (with any necessary modifications), facilitate social connections through senior centres, address sleep issues with practical measures, and consider mindfulness-based approaches.

- Specialised Nutritional Strategies for Multimorbidity

Nutritional adjustments can guide multiple conditions simultaneously. For cardiac-renal concerns: use low-sodium (2g/day), modified protein diets. For malnutrition with inflammation: protein-energy supplements with omega-3 fatty acids (2.2g EPA/DHA daily). For diabetes plus kidney disease, plant-based protein can aid in maintaining renal function. For cognitive decline: Mediterranean patterns with extra virgin olive oil and nuts. For frailty: diets high in protein (1.2–1.5g/kg/day) supplemented with vitamin D.

7. Implementing Regular Monitoring Protocols

Successful care plans adapt over time. Schedule follow-up appointments based on patient stability, keep tabs on function and side effects, adjust treatment intensity as conditions evolve, and document all changes. Revisit advance care preferences if health status shifts significantly.

8. Addressing Psychosocial Dimensions

Mental health often influences physical outcomes. Screen for depression and anxiety, evaluate caregiver strain, and supply links to community help. Assess economic barriers periodically and revise plans to fit what’s financially viable.

9. Advance Care Planning Integration

Discussing end-of-life preferences, ICU interventions, or life-support measures ensures care aligns with patient wishes. Such planning increases quality of life and helps avoid unwanted treatments.

10. Practical Implementation Framework

Care for older adults with multiple chronic conditions and numerous medications calls for:

- Focusing on personal goals above disease-specific targets.

- Taking deprescribing as seriously as prescribing.

- Periodically overhauling medication lists rather than simply adding more.

- Collaborating across an interdisciplinary care team.

- Monitoring outcomes beyond lab numbers, inclusive of function and daily comfort.

- Addressing cost constraints to keep treatments attainable.

- Enlisting caregivers as key partners in care.

Polypharmacy

Polypharmacy is defined simply as the use of multiple medications by a patient. The precise minimum number of medications used to define "polypharmacy" is variable, but generally ranges from 5 to 10.

Problematic polypharmacy is defined as the use of multiple medications in a way that is not considered to be appropriate. Polypharmacy (taking five or more medications) impacts roughly 40% to 65.1% of older adults, with higher figures seen in those who have heart disease (up to 61.7%) or diabetes (up to 57.7%). Hospital stays often add an average of two new drugs, further complicating regimens.

The Issue of Polypharmacy

It is of particular concern in older people

- Older individuals are at greater risk for ADES due to metabolic changes and decreased drug clearance is associated with ageing.

- Polypharmacy increases the potential for drug-drug interactions and for prescription errors of potentially inappropriate medications.

- Adverse drug interactions affect around half of older adults on five to nine medications, contributing to nearly 30% of hospital admissions and ranking among the top causes of death in the United States.

- Polypharmacy was an independent risk factor for hip fractures.

- Polypharmacy increases the possibility of "prescribing cascades". A prescribing cascade develops when an ADE is misinterpreted as a new medical condition and additional drug therapy is then prescribed to treat this medical condition.

- Use of multiple medications can lead to problems with adherence in older adults, especially in patients with visual or cognitive impairment.

- Increases financial burden.

So a balance is required between over- and under-prescribing. Multiple medications are often required to manage older adults.

Depresribing Inappropriate Medications

The most widely used criteria for inappropriate medications are the

1. Beers Criteria

The most widely cited criteria used to assess inappropriate drug prescribing

The criteria are a list of medications considered potentially inappropriate in older adults, most likely to

Medications are grouped into categories:

- Those potentially inappropriate in most older adults- eg, benzodiazepines, anticholinergics, sulphonylureas, chronic use of PPI and NSAIDS.

- Those that should typically be avoided in older adults with certain conditions- eg, insulin should preferably be avoided in patients with dementia, ACE inhibitors avoided in patients with hyperkalemia, and beta blockers avoided in patients with asthma.

- Drugs to use with caution due to the potential for harmful adverse effects: aspirin.

- Drugs to use with caution due to the potential for drug drug in interactions.

- Drug dose adjustment based on kidney function- Eliquis, antibiotics, etc.

In another approach, a Drug Burden Index has been modelled, incorporating

- Drugs with anticholinergic or sedative effects

- Total number of medications

- Daily dosing

An increased drug burden for anticholinergic and sedative medications was associated

with impaired performance on mobility and cognitive testing

The total number of medications was not associated with impaired performance if sedatives and anticholinergics were excluded. A high Drug Burden Index has been correlated with increased risk for functional decline and increased risk of falls.

Anticholinergics are associated with many adverse effects when used in older adults

- Memory impairment

- Confusion

- Hallucinations

- dry mouth

- blurred vision

- constipation, ,

- urinary retention

- impaired sweating

- Can precipitate acute glaucoma

Increase the risk of community-acquired pneumonia

In essence, it's crucial to distinguish between necessary and unnecessary use of medications and to prioritise strategies that minimise potential harm and optimise medication regimens. This attempt can help improve patient outcomes, reduce healthcare costs, and enhance quality of life, especially in older adults.

Disclaimer- The information is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of M3 India.

About the author of this article: Dr. Apurva Jain is an MBBS, DNB Family Medicine, DAA, working as a Senior resident in the ESI hospital, Delhi.

-

Exclusive Write-ups & Webinars by KOLs

-

Daily Quiz by specialty

-

Paid Market Research Surveys

-

Case discussions, News & Journals' summaries