Acute Painful Loss Of Vision-Ophthalmic Emergency

M3 India Newsdesk Nov 09, 2022

This article, the third in a series on ophthalmic emergencies, discusses the symptoms and therapeutic care of ophthalmic disorders that can suddenly impair vision.

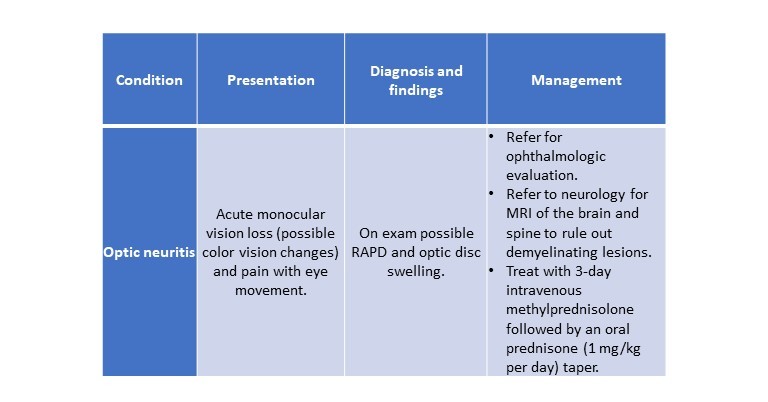

1. Optic neuritis

There are several possible causes of optic neuritis including:

- Autoimmune illness

- Infection, inflammation

- Para-vaccination immunological reaction,

- And multiple sclerosis

Young individuals are the most often affected.

Symptoms

- Monocular vision loss

- Eye discomfort

- Dyschromatopsia, are a common symptom in patients who have a sudden loss of vision (reduced contrast in colours).

Diagnosis

A relative afferent pupillary deficit (RAPD) may also be seen on inspection, however, involvement of the opposite eye may obscure this. In one-third of cases, diffuse optic disc oedema/swelling may be visible on direct ophthalmoscopy. Optic neuritis is diagnosed clinically based on the presence of the symptoms listed above.

Management

- Refer patients for further neurologic evaluation and gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain and spine to rule out the existence of demyelinating lesions and assess the risk of developing clinical multiple sclerosis.

- Intravenous corticosteroids have been the most effective treatment for optic neuritis.

- The Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial demonstrated that patients who received three days of high-dose intravenous methylprednisolone followed by an oral prednisone taper regained eyesight more quickly than those who received 14 days of oral prednisone (1 mg/kg per day).

- This difference, however, was eliminated after one month of therapy. The oral regimen did result in a twofold increase in the risk of recurrent ocular neuritis. Thus, in individuals with optic neuritis, initial therapy with oral prednisone 1 mg/kg per day is contraindicated.

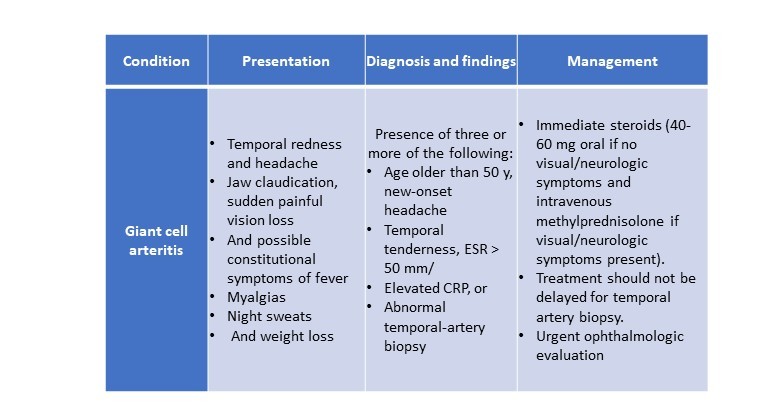

2. Giant cell arteritis

Giant cell arteritis (GCA), also known as temporal arteritis, often affects adults over the age of 50 years. It is a vasculitis with granulomatous manifestations that affects large and medium-sized arteries, including the ocular artery.

It needs prompt identification and treatment, as failure to do so may result in irreversible vision loss (up to 15% to 25% of cases) due to ischemic consequences of the illness in the afflicted eye. Urgent treatment is also required to safeguard the unaffected eye, which is at a higher risk of infection.

Symptoms

A typical presentation would include:

- A temporal headache

- Jaw claudication

- Temporal pain

- Sudden/severe vision loss

- Low-grade fever

Other constitutional symptoms such as lethargy, myalgias, night sweats, and weight loss. However, up to 20% of individuals with GCA-related visual loss have no systemic symptoms, making diagnosis problematic.

Additionally, some patients may have had brief vision loss, eye discomfort, or diplopia in the weeks before presentation owing to transitory optic nerve head ischemia.

Diagnosis

- According to the American College of Rheumatology, GCA is diagnosed when three or more of the following criteria are present: age greater than 50 years, new-onset headache, tenderness to temporal artery palpation or decreased pulsation, an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) greater than 50 mm/h, or an abnormal temporal-artery biopsy. However, if there is a strong suspicion of GCA, therapy should not be delayed until a temporal artery biopsy is performed.

- If urgent laboratory tests or an invasive biopsy cannot be acquired in the outpatient environment, the patient should be transferred to the emergency department for early examination. A complete blood count, ESR, and C-reactive protein (CRP) level should be obtained as part of the workup.

Management

If no visual or neurologic symptoms are present, the patient is first treated with oral prednisone at a dose of 40 to 60 mg (about 0.75 mg/kg) each day. In the occurrence of such symptoms, greater doses of oral prednisone or intravenous methylprednisolone of 1 to 1.5 mg/kg should be initiated.

3. Central retinal artery occlusion

Because irreparable ischemia damage to the retina may develop in as little as 90 minutes, central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO) is an ophthalmic emergency. It is called an "ocular stroke," and the chance of having an ischemic stroke with major artery involvement is elevated significantly in the first 1 to 4 weeks after CRAO diagnosis.

Symptoms

- Patients may appear with a brief, painless loss of vision in one eye.

- If one of the smaller distal arteriolar branches is damaged, a patient may have partial vision loss. Additional history-taking may show earlier occurrences of transitory, painless visual loss.

- CRAO is predisposed to the same risk factors as other cardiovascular events, including cigarette smoking, hypertension, a high body mass index, elevated blood cholesterol levels, diabetes, and heart illness.

- Additionally, hypercoagulable illnesses such as antiphospholipid antibody syndrome and autoimmune disorders might contribute to an individual's risk.

Diagnosis

- RAPD, pale, non-perfused retina, and a "cherry-red patch" owing to the vivid red appearance of the fovea during the funduscopic examination may be seen during the inspection.

- If, however, the patient appears in the early stages, these indications may be absent or may take several hours to manifest. Due to the sluggish segmental blood flow in the retinal arterioles and veins, a "box-car" pattern may also be observed; however, emboli inside arterioles are not always visible.

- There are no established therapeutics for occlusions of the retinal arteries. Digital massage to dislodge the clot and diminish the ischemic region, anterior chamber paracentesis, and carbogen breathing (4 to 7% carbon dioxide, 93 to 96 per cent oxygen) have all been recommended as therapy possibilities, but visual results are often poor.

Management

- Acute CRAO patients should be started on the full dosage of aspirin and sent to the emergency room for carotid imaging and neurologic assessment.

- Within 1 to 2 weeks of presentation, they should receive a brain MRI, echocardiogram, and 48-hour Holter monitoring.

- Additionally, any patients with CRAO who are over 60 years of age, or who are over 50 years of age and have headache, scalp discomfort, or jaw claudication, should be tested for GCA using a complete blood count, CRP, and ESR. Dietary changes, smoking cessation, and statin therapy are all recommended for people with CRAO.

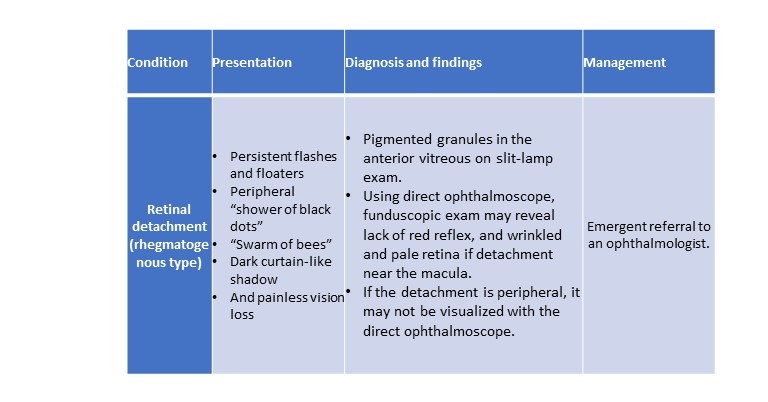

4. Retinal detachment

The term "retinal detachment" refers to the separation of the neurosensory retina from the underlying retinal pigment epithelium. While this is an uncommon disorder, it is considered an emergency because early identification and treatment may avoid photoreceptor ischemia degradation and irreversible vision impairment.

Symptoms

- Patients may experience blinding flashes in one eye, followed by a "shower of black dots" or a "swarm of bees," and diminished visual acuity.

- Others may experience transient, recurring flashes and floaters, as well as the movement of a black curtain or shadow from their periphery to central vision.

- Patients may also have a loss of central vision or (in rare cases) entire light sensitivity if the macula is compromised.

- Age (due to age-related posterior vitreous detachment [PVD]), high myopia, trauma, diabetes (specifically a risk factor for tractional retinal detachment), lattice degeneration, previous cataract surgery, family history of retinal detachment, and a personal history of previous detachment are all risk factors for developing a retinal detachment.

- Additionally, retinal detachments are connected with congenital-developmental defects such as Stickler syndrome, Marfan syndrome, and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

Diagnosis

- Prior to pupillary dilation, visual acuity should be assessed during the test. If a slit lamp is available, the presence of pigmented granules in the anterior vitreous (as seen by an oblique slit beam) may indicate a probable separation.

- A direct ophthalmoscope may be used to observe the presence or absence of a red reflex, which may suggest a detached retina or vitreous haemorrhage.

- Given the direct ophthalmoscope's small field of view, a detachment near the macula (the region surrounding the fovea that produces detailed vision) would seem wrinkled, opaque, and pallid.

- Indirect ophthalmoscopy, on the other hand, is required to thoroughly check the central and peripheral retina for a break.

Management

- If a retinal detachment is suspected, the patient must immediately be sent to a surgical vitreoretinal specialist for immediate treatment.

- PVD, which is an age-related process of vitreous degeneration and shrinking, is a natural and frequent occurrence in adults over the age of 40year.

- While PVD is more prone to induce flashes and floaters, patients who exhibit these symptoms should still be sent to an ophthalmologist for a dilated eye test.

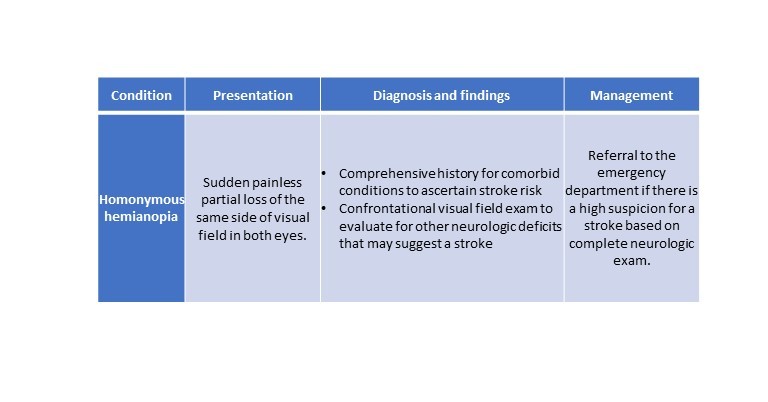

5. Homonymous hemianopia

Homonymous hemianopia (HH) is a visual field impairment characterised by loss of vision on the same side in both eyes. A partial or total HH may arise depending on the location of the neuro-ophthalmic tract affected.

Symptoms

Sudden vision loss in this pattern may be caused by a variety of various conditions, including tumours and seizures; however, stroke is the most prevalent cause, and urgent diagnosis is important.

Diagnosis

A confrontational visual field examination and a general neurologic examination should be done on high-risk elderly or post-stroke patients to rule out a probable stroke. A thorough history and assessment of comorbid illnesses that enhance the risk of stroke may assist in determining the potential of a neurologic event.

Management

If the HH or any other sort of visual field impairment is acute or subacute, the patient should be sent to an emergency hospital for evaluation of a neurologic event.

Conclusion

Conclusion

Recognising and treating ocular crises promptly is critical for maintaining visual acuity and achieving the greatest overall ocular and systemic outcomes. For patients with acute eye problems, we expect that by giving a succinct description and approach to frequent ophthalmic emergencies, doctors would be able to quickly evaluate and treat them.

This is part 3 of the article. Click here to read the previous parts- A guide to ophthalmic emergencies, A Treatment Guide to Various Infections For Ophthalmic Emergencies

Click here to see references

Disclaimer- The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of M3 India.

About the author of this article: Dr Monish Raut is a practising super specialist from New Delhi.

-

Exclusive Write-ups & Webinars by KOLs

-

Daily Quiz by specialty

-

Paid Market Research Surveys

-

Case discussions, News & Journals' summaries