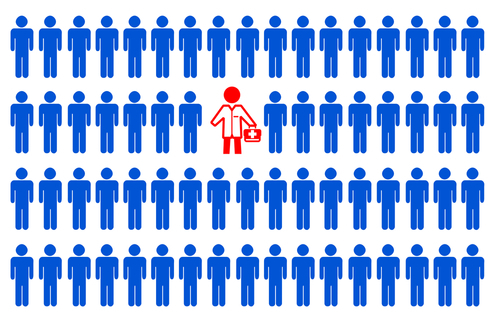

A peek into the 'one doctor-many patients' crisis in India

M3 India Newsdesk Feb 09, 2018

Doctor-patient ratio in India hasn’t improved since 1991. At the current rate at which new doctors are being churned out, the country will need at least 10 years to match WHO’s standard.

Doctors working in India should not expect their workload to reduce anytime soon as the country is a decade away from achieving the doctor-patient ratio the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends.

Here is why the pressure of work will not only continue but increase with time:

Acute shortage of doctors resulting in manifold increase in disease outbreaks

A senior official of the Union health ministry said the prevalence of quacks--untrained, unregistered medical practitioners--in villages and them being the rural population's first line of defense has contributed to the surge in disease outbreaks. He said that according to the government rules, any outbreak should be immediately reported to the ministry so that action can be initiated to curb its spread. However, quacks don’t follow this practice as they are not a part of the government mechanism.

According to the Integrated Disease Surveillance Project (IDSP) of the Union health ministry, 553 outbreaks were reported in the country in 2008. In 2016, the number of reported outbreaks stood at 2,679. In these eight years, the number of outbreaks increased by almost five times. Most of these outbreaks were of acute diarrhoeal diseases, food poisoning and measles.

Wrong prescription by quacks leading to complications

Quacks often end up prescribing wrong medicines or advising incorrect treatment, which leads to complications. It is only when their condition worsens that they head to hospitals. This leads to increased footfall in urban hospitals and increased pressure on doctors in the city.

Dr AK Srivastava, Chief Medical Superintendent of the Gorakhpur-based BRD Medical College--where hundreds of children die every post-monsoon season owing to encephalitis--said delayed treatment owing to quacks is why their hospital sees high mortality rate.

Delay in treatment can cause irrecoverable damage and unnecessary health complications resulting in high work pressure on city doctors

Rural population's lack of access to doctors forcing them to try home cures

Dr Venkatesh Reddy, co-founder of Silicon City Super Speciality Hospital and Trauma Center, Bangalore, said in their hospital too, most of the patients from rural areas come in the advanced stages of illness.

He added that because of this issue, there is a lot of pressure on specialist doctors in the city. He said non-availability of trained medical practitioners in rural areas is ending up increasing the burden, and difficulty level of treatment, of doctors in cities.

The situation is going to be grim for doctors working in states like Bihar, Chhattisgarh, and Maharashtra that fare worse with one doctor serving more than 25,000 people.

Too few new doctors

The doctor-patient ratio in India has seen no improvement between 1991 and 2015.

The rate at which India is getting new doctors every year indicates that the country would need another decade to achieve the World Health Organization's (WHO) recommended doctor-patient ratio of 1:1,000. It implies that the burden of overworked doctors, mainly specialists, is not going to alleviate anytime soon. According to the National Health Profile 2015, there’s only one government doctor for every 11,528 people in India.

“The number of doctors passing from colleges is so low that even if government hires all of them, the problem cannot be solved,” asserted the aforesaid Union health ministry official, who has worked with the United Nations Development Programme for about five years.

India could add only 2.07 lakh doctors in public and private hospitals between 2007 and 2014. To cater to the present population, the country needs another three lakh doctors. Moreover, of India's total doctor population of 9.3 lakh, only 1.06 lakh are government allopathic doctors.

The situation is going to be particularly grim for doctors working in states such as Bihar, Chhattisgarh and Maharashtra, where one doctor serves more than 25,000 people. Bihar, with a population of 10 crore could add only 3,179 doctors between 2007 and 2014. At the current rate of adding doctors, the eastern state will take another 140 years to match the WHO-recommended doctor-patient ratio. UP will need another 75 years, and Chhattisgarh 30 years.

Southern states added more doctors compared to the rest of the country. In the seven-year period starting 2007, Tamil Nadu added 23,754 doctors, Karnataka 25,432, Kerala 9406, and Andhra Pradesh 15,233. This was equal to one-third of the total doctors added in all states across the country.

While concentration of medical colleges in these regions bodes well for them, the other, more highly populated, areas face a severe shortage of doctors. This means doctors serving in these regions cannot expect their workload to reduce anytime soon.

Here are a few steps taken by the government to increase the number of doctors in the country:

I. Relaxation in the norms for setting up of a medical college in terms of requirement for land, faculty, staff, number of beds, and other infrastructure.

II. Strengthening/upgradation of existing State Government/Central Government Medical Colleges to increase MBBS seats with fund sharing between the Central Government and States.

III. Establishment of New Medical Colleges by upgrading district/referral hospitals preferably in underserved districts of the country with fund-sharing between the Central and State governments.

IV. Enhancement of maximum intake capacity at MBBS level from 150 to 250.

V. Enhancement of age limit for appointment/extension/re-employment in posts of teachers/dean/principal/director in medical colleges from 65-70 years.

VI. DNB qualification has been recognized for appointment as faculty to take care of shortage of faculty.

Every now and then, there is news of the government planning to launch premium AIIMS-like institutes in the country or build medical colleges in the under-served areas. While these institutes will serve tremendous purpose to the people, how is the government planning to address the gross shortage of faculty at such teaching hospitals? Most medical professionals are reluctant on practicing in rural areas, because of patient overload and lack of adequate facilities.

To make things worse, a recent bill which should have sorted the issue by making it mandatory for medical students to serve in rural areas for a stipulated period decided to make things worse by allowing non-doctors to practice, only encouraging quackery in the process.

Sadly, what continues to remain unchanged are the end sufferers of the system- the poor and under-served sections of the society residing in rural areas that have no access to basic healthcare or registered medical professionals.

-

Exclusive Write-ups & Webinars by KOLs

-

Daily Quiz by specialty

-

Paid Market Research Surveys

-

Case discussions, News & Journals' summaries