Hepatitis: Know More about Diagnostic & Treatment Modalities

M3 India Newsdesk Jul 28, 2022

Hepatitis is a significant global killer, equivalent to HIV, TB, and malaria. Hence, it is of extreme importance to understand its clinical course, diagnosis and management for the disease to be eradicated completely.

Viral hepatitis concerns increasing in India

- Hepatitis in India and recover entirely without clinical sequelae.

- Hepatitis B and C may lead to chronic infection and sequelae such as cirrhosis and hepatocellular cancer.

- Cirrhosis and hepatocellular cancer, chronic hepatitis B and C sequelae account for 90% of associated fatalities. Poor access to therapy increases mortality from HBV and HCV-associated cirrhosis and hepatocellular cancer.

- Combining prevention and treatment makes long-term hepatitis B and C eradication possible.

- Through the National Health Mission, the Indian government will provide free diagnosis and treatment for viral hepatitis.

Due to insufficient data, the country's illness burden is unknown, literature reveals:

- HAV- It causes 10-30% of acute hepatitis and 5-15% of acute liver failure in India.

- HEV- It causes 10-40% of acute hepatitis and 15-45% of acute liver failure.

- Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) in the general population is 1-3 per cent.

- Anti-HCV antibody prevalence- 0.09-15% in the general population.

- Hepatitis C in India.

- HBV- In India, chronic HBV causes 40-50% of HCC and 20-30% of cirrhosis.

- Chronic HCV - 12-32% of HCC and 12-20% of cirrhosis.

Hepatitis A infection

HAV is a non-enveloped RNA picornavirus with 4 genotypes. This virus is transmitted fecally orally. Incubation lasts 4 weeks. Poor hygiene and overcrowding promote HAV spread. The presence of excretion in the stool only lasts 7-14 days after the beginning of the clinical disease and is indicative of an acute HAV infection. There hasn't been any evidence of a carrier state. Safe, effective inactivated attenuated vaccination is available.

Clinical course

- HAV has a 15-45-day incubation period.

- Acute viral hepatitis has systemic, varied prodromal symptoms.

- Low-grade fever, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, lethargy, malaise, arthralgias, myalgias, headache, photophobia, pharyngitis, cough, and coryza may precede jaundice by 1-2 weeks.

- Before clinical jaundice, patients may detect dark urine and clay-coloured faeces. Constitutional prodromal symptoms lessen with clinical jaundice.

- The liver becomes enlarged and tender, causing right upper quadrant pain.

Laboratory diagnosis

- HAV is transiently present in the blood throughout the incubation phase, hence anti-HAV antibodies are necessary for diagnosis.

- IgM antibodies against HAV may be detected 5-10 days before symptoms and last 6 months.

- Anti-HAV IgM indicates acute infection.

- During convalescence, HAV IgG antibodies become predominate and are detectable forever.

- Anti-HAV total antibodies (IgG and IgM) or specific IgG (but anti-HAV IgM negative) suggest prior infection or immunisation.

- Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and ALT rise during prodromal sickness and precede bilirubin elevation. Jaundice occurs when serum bilirubin is >2.5 mg/dL.

Management

- Antiviral medicines have no function in the treatment of HAV infection. Almost of people with hepatitis A who were previously healthy recover fully with no clinical complications.

- The case fatality rate is very low (0.1%), but increases with age and the presence of chronic underlying illnesses. Improving social circumstances, particularly congestion and squalor, is the most effective means of preventing infection in a society.

Hepatitis B infection

HBV, a virus with double-stranded DNA, is a member of the hepadnavirus family. HBV infection is a worldwide health concern. In places with high incidence, perinatal transmission and sometimes horizontal transfer early in life are most prevalent. Additionally, sexual contact and percutaneous transfer contribute to HBV transmission.

Clinical course

- In both acute and chronic illnesses, the range of clinical symptoms of HBV infection differs.

- Subclinical or anicteric hepatitis are among the acute phase symptoms.

- The HBV incubation time ranges from 30 to 180 days.

- Asymptomatic carrier status, chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, and HCC are examples of chronic phase manifestations.

- Acute and persistent infections may also cause extrahepatic symptoms.

Clearance of persistent HBV infection

Some chronic HBV-infected people become HBsAg-negative. The estimated yearly rate of delayed clearance of HBsAg in Western patients is between 0.5 and 2 per cent, whereas the rate in Asian nations is substantially lower (0.1 to 0.8 per cent). In the majority of cases, HBsAg-negative patients looked to have a favourable prognosis. After HBsAg clearance, progression to cirrhosis and hepatic decompensation is uncommon in the absence of other causes of liver damage. Those with HCV or hepatitis D virus (HDV) co-infection, cirrhosis, or who are older than 50 years at the time of HBsAg clearance should continue to be monitored for hepatocellular carcinoma.

Laboratory diagnosis

During the acute phase, laboratory testing indicates elevated levels of alanine and aspartate aminotransferases (ALT and AST), with ALT levels often exceeding those of AST by 1000 to 2000 international units per litre (IU/L). The blood bilirubin levels of people with anicteric hepatitis.

Evaluation of the severity of liver disease

A comprehensive evaluation should include:

- Clinical evaluation for cirrhosis features and evidence of decompensation.

- Measurement of serum bilirubin, albumin, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), and prothrombin time; as well as a complete blood count, including platelet count.

- Full blood count, including platelet count. Ultrasonography and alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) testing for periodic monitoring for HCC, and endoscopy for varices in patients with cirrhosis are additional common diagnostics.

Non-invasive tests (NITs)

Due to the restricted availability and accessibility of liver biopsies, non-invasive approaches for determining the stage of liver disease are replacing liver biopsies and have been validated in adults with CHB. Blood and serum fibrosis indicators, such as APRI and FIB-4, or transient elastography (FibroScan) can rule out advanced fibrosis. APRI (AST-to-platelet ratio index) and FIB 4 are the primary non-invasive tests (NIT) for determining the existence of cirrhosis (APRI score >2: FIB 4 >3.25 in adults). Transient elastography (e.g. FibroScan) may be the preferred NIT in areas where it is readily accessible and the cost is not a significant factor.

- APRI and FIB-4 can be readily calculated by the following formulae -

- APRI = (AST/ULN) x 100) / platelet count (109 /L)

- FIB-4 = (age (yr) x AST (IU/L)) / (platelet count (109 /L x [ALT (IU/L)1/2])

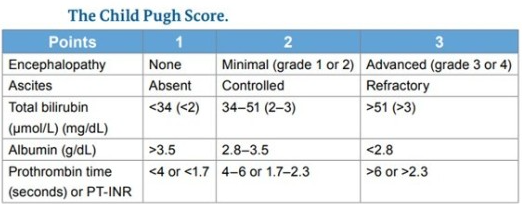

Determining the cirrhosis severity

Prior to initiating therapy, it is crucial to determine the severity of cirrhosis. Depending on clinical and laboratory criteria, the Child-Pugh Score classifies individuals as Class A, B, or C based on the severity of the liver disease. Class C is the most severe kind of liver disease. Certain HCV treatments are contraindicated for patients with Child-Pugh Class B and C cirrhosis or cirrhosis that has decompensated. The Child-Pugh Score is shown in the following table.

- Child-Pugh Class A: 5-6 points

- Child-Pugh Class B: 7-9 points

- Child-Pugh Class C: 10-15 points

Management of hepatitis

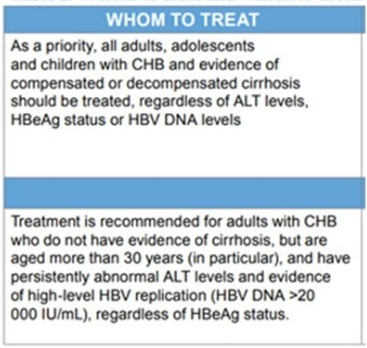

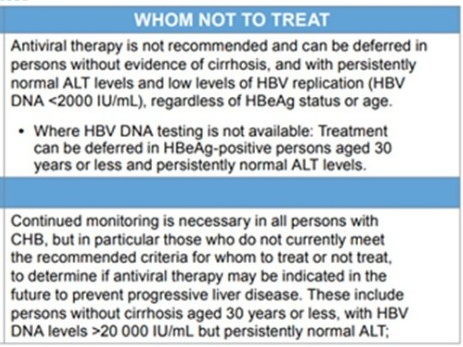

1. Who should be treated?

As therapy for hepatitis B make treatment decisions complicated.

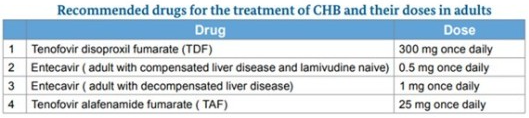

The recommended medications and dosages for the treatment of CHB in adults

2. When to terminate therapy?

- All individuals with cirrhosis based on clinical evidence (or APRI score >2 in adults) need lifetime treatment with Nucleoside analogues (NAs) and should not quit antiviral medication due to the danger of reactivation, which may also result in severe acute-on-chronic liver damage.

- The termination of hepatitis B treatment is often not advised and should only be performed at specialist clinics under the supervision of the required competence.

- The decision to quit treatment needs careful assessment of the danger of virological recurrence, decompensation, and mortality upon withdrawal vs the expense of continuing medicine and monitoring.

- Patients with cirrhosis should not quit antiviral treatment due to the danger of reactivation, which might result in decompensation and mortality.

3. Discontinuation may be considered for individuals without cirrhosis

- With sustained HBsAg loss one year following consolidation therapy; (regardless of prior HBeAg status or availability of HBV DNA levels)

- Loss of HBeAg and seroconversion to Anti-HBe after one year (ideally three years) of further therapy with consistently normal ALT levels and undetectable HBV DNA levels.

- Careful long-term monitoring for reactivation using serial 3-6 monthly HBeAg, ALT, and HBV DNA readings is required for people who have ceased therapy and are contemplating retreatment. Relapse may occur after the conclusion of NA treatment. Retreatment is advised if persistent symptoms of reactivation are seen (HBsAg or HBeAg becomes positive, ALT levels increase, or HBV DNA becomes detectable again)

Hepatitis C infection

Clinical course of hepatitis C infection

- Infected syringes, needles, and blood transfusions spread hepatitis C.

- Heterosexual couples seldom transmit HCV sexually. It's frequent among HIV-positive MSM.

- In 4–8% of births to women with HCV and 10.8–25% of births to women with hiv and HCV co-infection, HCV is transmitted to the kid.

- Chronic hepatitis is frequently mild and defined by variable aminotransferase levels; >50% chronicity, leading to cirrhosis in >20%.

- Chronic HCV infection is typically asymptomatic and seldom life-threatening. 15–45% of infected people resolve acute HCV within six months without therapy.

- The remaining 55–85% of people will have chronic HCV infection if untreated. Chronic HCV may induce cirrhosis, liver failure, and HCC. 15–30% of chronic HCV patients will develop cirrhosis within 20 years.

- 2–4% of cirrhotics develop HCC each year.

Treatment of viral hepatitis C in adults

People with HCV can get a wide range of diseases, from mild fibrosis to cirrhosis and HCC.

- Compensated cirrhosis may develop into decompensated cirrhosis with ascites, oesophageal and gastric varices, and then to life-threatening liver failure, renal failure, and sepsis. 2–4% of cirrhotics develop HCC each year.

- Decompensated liver disease is diagnosed by clinical exam and laboratory monitoring, thus patients must be carefully examined before treatment.

- Liver biopsy or non-invasive procedures may determine the disease stage.

- Chronic HCV infection causes end-stage liver disease (cirrhosis), ascites, variceal haemorrhage, severe infections, HCC, and liver-related mortality globally. If HCV sufferers are not treated, they face a significant financial cost. HCV causes 495,000 deaths worldwide and 37,000 fatalities in India in 2015.

Who should be treated?

Anyone who has been diagnosed with hepatitis C virus infection (viremia+) requires therapy. Various factors will determine the length of therapy,

- Cirrhosis vs. non-cirrhosis

- Decompensation (ascites, variceal haemorrhage, hepatic encephalopathy, or infection(s), treatment-naive vs. treatment-experienced

- Treatment-naive vs. treatment-experienced (IFN, Direct-acting antivirals DAAs, etc).

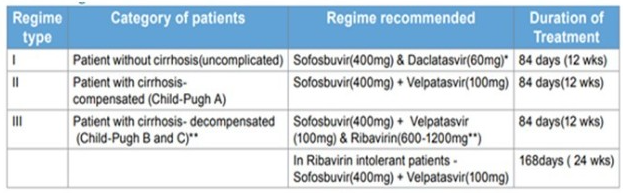

Which regime should I use?

In India, DAAs are the recommended first-line therapy. The DAA combination and treatment duration will be determined by the presence or absence of cirrhosis as well as the viral genotype.

When a patient is referred to a Tertiary Care Center with Acute Liver Failure

When to refer?

When the patient's sensorium changes in any way and the INR rises over 1.5, it's time to refer.

Where to refer?

- Shift the patient to a specialist critical care unit with the ability to offer airway and ventilator control (tertiary care unit)

- A liver transplantation facility is available (if the patient is willing)

How to transport the patient?

- Before transferring, a thorough conversation between the transferring and receiving physicians/teams is required.

- Intubate and sedate the patient in the event of a growing hepatic encephalopathy to enable a controlled and safe transfer

- Appropriate fluids should be supplied for continuing volume resuscitation.

- The patient should be kept normoglycemic.

- Vasopressors should be prepared and ready, as well as mannitol, in case of increased intracranial pressure during transportation.

Guidance from WHO recommendations on prevention

1. Infant and neonatal hepatitis B vaccination

hepatitis B vaccination should be given to all newborns as soon as feasible after delivery, ideally within 24 hours, followed by two or three doses.

Traditionally, the basic hepatitis B vaccination series consists of three vaccine doses (i.e. one monovalent birth dose followed by two monovalent or combined vaccine doses). For programmatic reasons (for example, one monovalent birth dose followed by three monovalent or mixed vaccination doses), four doses may be given according to national regular immunisation programme schedules. The basic series of three doses with proper intervals apply to older children and adults.

2. Passive immunisation against hepatitis B with HBIG

The use of HBIG for post-exposure prophylaxis confers temporary protection. In addition to HBV vaccination, HBIG prophylaxis may be beneficial for the following reasons: Infants born to HBsAg-positive mothers, especially if they are also HBeAg-positive. Protection against perinatally acquired infection established by immediate HBV vaccination (given within 24 hours) may not be substantially enhanced by the addition of HBIG in full-term neonates delivered to women who are HBsAg-positive but HBeAg-negative.

3. Catch-up vaccination strategy against hepatitis B

To speed the establishment of population-based immunity and reduce the incidence of acute hepatitis B, time-limited catch-up efforts targeting unvaccinated persons in older age groups may be required.

4. Hepatitis B patients

- General strategies for lowering HBV transmission Individuals who test positive for HBsAg should: If neither partner is HBV-immune nor has been vaccinated, condoms should be used correctly and consistently during sexual activity. not share toothbrushes, razors, or other personal care goods; not give blood, organs, or sperm; observe universal precautions for open wounds or bleeding.

- HBV vaccination of household and sexual contacts.

- Reduce alcohol consumption to slow disease progression.

Significant alcohol use (>20 g/day in women and >30 g/day in males) might hasten the development of cirrhosis caused by HBV and HCV.

WHO recommendations on prevention of HBV infection in healthcare settings

1. Recommendations

- Hand hygiene: including surgical hand preparation, hand washing and use of gloves

- Safe handling and disposal of sharps and waste

- Safe cleaning of equipment

- Testing of donated blood

- Improved access to safe blood

- Training of health personnel TABLE 10.1.

2. Important additional recommendations for HBV post-exposure prophylaxis after needlestick injury, sexual exposure, or mucosal or percutaneous (bite) HBV exposure

- Wounds should be washed with soap and water, and mucous membranes flushed with water.

- The source individual should be screened for HBsAg, hiv and HCV antibodies.

- HBsAg, anti-HBs and IgG anti-HBc should be checked in the exposed individual, to assess whether the individual is infected, immune or non-immune to hepatitis B.

- If the source individual is HBsAg positive or status is unknown, HBIG (0.06 mL/kg or 500 IU) is given intramuscularly and active vaccination commenced (0, 1 and 2 months) if the exposed individual is nonimmune. HBIG and vaccines should be given at different injection sites. HBIG is repeated at 1 month if the contact is HBeAg positive, has high HBV DNA levels or if this information is not known. If the exposed individual is a known non-responder to HBV vaccination, then two doses of HBIG should be given 1 month apart.

- Anti-HBs titres should be measured 1–2 months after vaccination.

3. Safety of injections in healthcare settings

Injection practices worldwide and especially in LMICs include multiple, avoidable unsafe practices that ultimately lead to large-scale transmission of bloodborne viruses among patients, healthcare providers and the community at large. Unsafe practices include, but are not limited to, the following prevalent and high-risk practices:

- Reuse of injection equipment to administer injections to more than one person, including the reintroduction of injection equipment into multidose vials, reuse of syringe barrels or of the whole syringe, informal cleaning and other practices.

- Accidental needlestick injuries in healthcare workers, occur while giving an injection or after the injection, including recapping contaminated needles and handling infected sharps before and after disposal.

- Overuse of injections for health conditions where oral formulations are available and recommended as the first-line treatment.

- Unsafe sharps waste management, putting healthcare workers, waste management workers and the community at large at risk. Unsafe management of sharps waste includes incomplete incineration, disposal in open pits or dumping sites, leaving used injection equipment in the hospital laundry, and other practices that fail to secure infected sharps waste.

- WHO guidelines in 2015 will provide recommendations on the use of safety-engineered syringes for intramuscular, intradermal and subcutaneous therapeutic injections in healthcare settings (www.who.int/injection_safety/en). This guidance will help prevent the reuse of syringes on patients and decrease the rate of needle-stick injuries in healthcare workers related to injection procedures.

- It will complement existing WHO best practices and the toolkit for injections and related procedures, published by WHO in 2010 (69), which notes the importance of a sufficient supply of quality-assured syringes and matching quantities of safety boxes.

Considerations for management of healthcare workers

- HBV screening and immunisation require special concern for healthcare workers; unfortunately, this is not routinely practised in LMICs.

- Surgeons, gynaecologists, nurses, phlebotomists, personal care attendants, and dentists who are HBsAg positive and perform exposure-prone operations should be considered for antiviral medication to reduce direct transmission to people.

- Before continuing exposure-prone procedures, they should take a powerful antiviral medication with a high barrier to resistance (i.e. entecavir or tenofovir) to reduce HBV DNA levels to undetectable or at least to 2000 IU/mL, according to 2013 ARV recommendations.

- Following needlestick or other occupational exposures, post-exposure prophylaxis should be explored.

GPs serve important roles as "gatekeepers" to the healthcare system, providing primary preventive and curative health treatments. As a result, it is critical to provide GPs with comprehensive information on prevalent health issues as well as treatment options. In order to avoid HBV and HCV infections, GPs have a significant amount of responsibility for the diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of infected patients.

WHO calls for the elimination of the disease by 2030

On World hepatitis Day, the UN health agency noted that every 30 seconds a person dies from a hepatitis-related condition and urged all nations to eradicate this avoidable disease by 2030.

Click here to see references

Disclaimer- The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of M3 India.

The present article gives an overview of hepatitis in general. Readers are requested to go through references for further detailed reading.

The author is a practising super specialist from New Delhi.

-

Exclusive Write-ups & Webinars by KOLs

-

Daily Quiz by specialty

-

Paid Market Research Surveys

-

Case discussions, News & Journals' summaries